By Wendell Steavenson

On September 30th I watched the last few cars of Armenian refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh drive over the border into Armenia. In the space of a few days, their enclave within Azerbaijan had ceased to exist. Less than a fortnight before, on September 19th, Azeri forces had routed the positions of the Karabakh Armenians. After 30 years of failed negotiations and intermittent fighting, the final battle lasted one day. Then the entire population of 100,000 people fled. Two days earlier, the president of Nagorno-Karabakh announced that from January 1st 2024, Nagorno-Karabakh would cease to exist.

Now, as I looked out from the heights, the Lachin corridor, the sliver of road that connected Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, was empty. For five days it had been crammed with a traffic jam of cars, vans and tractors snaking 70km from Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, to the border. A troop of kids from the nearby village pointed out the Azerbaijani military positions on nearby ridges. There was no evidence of Armenian armed forces, not even a single sandbag. Several trucks full of Russian soldiers, who had supposedly been peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh, rumbled past. Russia, Armenia’s traditional ally in the region, had not intervened to prevent the Azerbaijani attack.

In the town of Goris, set in a gorge around 20km from the border on the Armenian side, volunteers had set up tents, dispensing food and clothes in the main square. The faces of the refugees were hollow and drawn from exhaustion. Some wailed against their loss or sobbed, most were simply silent and spent. I spoke to several families who described their flight, as volunteers put them onto buses and minivans to lodge in hotels and borrowed apartments in towns across Armenia. None said they had seen an Azerbaijani soldier during the past week, until the last checkpoint before leaving Karabakh.

Yura Baluyan and his family found shelter in a holiday camp on the shore of Lake Sevan. The owners were putting them up free in simple wooden chalets. They were now refugees. On the terrace stood two plastic water bottles filled with dried beans which the family had grown in Karabakh. Yura’s grandchildren played with puppies under the pine trees. His family had fought for decades to preserve Nagorno-Karabakh’s parlous de facto independence. “This is the end of the struggle,” he said sadly.

Baluyan was born in 1946 in the village of Aknaghbyur in Nagorno-Karabakh, then an autonomous region within the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan, part of the USSR. Karabakh is a region of sharply folded hills, of forests and gorges. To the west are the upland plateaus of Armenia, in those days a donkey trek over steep, winding paths. To the east lies the dun Azeri plain that stretches to Baku on the oil-rich shore of the Caspian sea.

After completing his military service Yura worked at the collective farm, married Bela, a kindergarten teacher, and had three sons: Anatoly, Hrayr and Hayk. Their village comprised little more than a few dozen families. Bela lamented the fact that they had no church – the family walked over the river to a nearby village for weddings and funerals.

There were no Azeris living in Aknaghbyur itself, but Azeri shepherds grazed their flocks in the hills. In the early 1970s Bela had studied in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians), a small mixed town of Azeris and Armenians perched on a dramatic cliff above the regional capital of Stepanakert. She remembered that, during the Soviet period, “most people had good relations.”

As the Soviet Union collapsed, violence between the Christian Armenians and the Muslim Azeris flared. Both sides killed people or deported them. In Stepanakert and Yerevan, the Armenian capital, huge demonstrations called for Nagorno-Karabakh to be transferred to Armenia, even though it was landlocked inside Azerbaijan.

The Armenians won the first Nagorno-Karabakh war, which was fought mainly between 1992 and 1994. Between 5,000 and 6,000 Armenians were killed. Azerbaijani deaths are estimated at between 10,000 and 30,000. As a result of the conflict, more than 200,000 Armenians were displaced from Azerbaijan; around 800,000 Azeris were displaced from Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, now under Armenian control.

Yura had a health condition and could not fight in that war. Still, he helped out, manning the radio in the village to keep families informed of news of casualties. Anatoly, the eldest boy, was old enough to join the war for the last few months. He remembered the joy when Shusha was liberated.

After the Armenian victory, there was a period of relative calm and prosperity in Nagorno-Karabakh, as money flowed in from the Armenian diaspora. A new tarmac road was built, connecting the enclave to Armenia. Yet the Armenians in Karabakh could never feel entirely comfortable. “Of course we were happy when we won,” Bela told me. “But inside our hearts we always carried some fear.” Like all men in Nagorno-Karabakh, the three Baluyan boys did military service for two years and Hrayr became a sergeant in the Karabakh defence force.

In September 2020 the Azerbaijani army, now modernised and well equipped, attacked. Over 44 days, it retook large parts of Karabakh that had been majority Azeri, along with some Armenian villages. Women and children evacuated from Aknaghbyur at the start of the fighting.

All three Baluyan brothers were mobilised and observed the force of the Azerbaijani invasion at first hand. Hrayr saw Turkish-made kamikaze drones blow up cars to make barriers to block roads. Hayk, called up as a reservist, was deployed to Lachin, but the men he was with didn’t know the terrain well. Artillery hit them on the road, inflicting casualties. They tried to take cover in the forest and woke up to find themselves surrounded by Azerbaijani troops. Eventually they withdrew, afforded safe passage by Russian peacekeepers. Anatoly, initially called up as a reservist, pulled back to defend Aknaghbyur, together with a couple of dozen men from the village. As the Azeris closed in, he went back alone to his house, to retrieve family documents. Perhaps he was spotted, as the Azerbaijanis started shelling. As he retreated through the woods, he watched Azeris set fire to several houses.

A ceasefire came into effect in November 2020. Russia, which saw the Caucasus as part of its sphere of influence, deployed peacekeepers. The agreement allowed Armenia to provide financial support to the Karabakh civil administration, but not to the armed forces. Karabakh’s defenders were left with only a handful of artillery pieces, tanks and trucks.

Armenians in Karabakh put their faith in the Russian presence, but Russia’s position became weaker after the war in Ukraine began. Azerbaijanis fired at farmers in their fields, the occasional bullet pinging against tractors. In 2022 Nikol Pashinyan, the prime minister of Armenia, who had come to power in a popular revolution and reoriented the country away from Russia towards greater co-operation with America and the European Union, formally recognised Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan. The Armenians in Karabakh were increasingly isolated. In December 2022 Azerbaijan closed the Lachin corridor connecting Karabakh to Armenia: it wanted supplies to come solely from Azerbaijan. The authorities in Stepanakert refused to accept imports from Azerbaijan. All the Armenian refugees I talked to had agreed with this decision. “For us it was better to die from starvation than to get supplies from the Azeris,” one old woman told me. The blockade began.

Hayk and his family were able to grow beans and potatoes, tomatoes and cucumbers in the garden in front of the hotel in Stepanakert where they lived. By the end of the summer the situation was dire. “We stood in long queues at the bakery, four or five hours at a time,” his daughter Elena,14, told me. “Sometimes we couldn’t get any bread at all.” Bella rendered pork fat when there was no more cooking oil in the shops. Prices became exorbitant: a single egg cost more than $1; a kilo of potatoes sometimes reached $7, if you could find any. “And even if someone had potatoes you couldn’t fetch them,” said Bella, “Because no one had any petrol.”

Buses stopped running over the summer and the electricity supply was intermittent. Anatoly couldn’t find painkillers for his back problem. In July, Hrayr’s baby son got a piece of nut lodged in his lung. Russian peacekeepers called three times before the Azerbaijanis let an ambulance take him to Armenia for emergency treatment.

Then at 1pm on September 19th, Azerbaijan attacked again.

It was a nightmare,” said Elena, Hayk’s daughter. “Everyone was crying, hugging each other and everyone was praying because everyone had a father and brothers at military positions.” Several shells fell inside Stepanakert. People spent the night in cold, dark basement shelters.

Hrayr, serving in the armed forces, watched Azerbaijani artillery arc over his position in the direction of Stepanakert, a few kilometres away. There was no mobile-phone signal so he couldn’t contact his family; communication with his commanders was also patchy.

Around 24 hours later, the Armenian leadership of Nagorno-Karabakh agreed to a ceasefire. The Azerbaijanis claimed they had taken more than 60 Armenian positions. There were hundreds of casualties on both sides.

I asked Hrayr how he had felt at the news of the ceasefire. He hung his head and sighed. “We knew that the lives of 100,000 people in Karabakh depended on us. We could either continue to fight or give up our weapons and guarantee the safety of these people. There was no other choice.”

”Hrayr waited at his position for three days before he learned that the Russians would provide safe passage. Finally on the evening of September 23rd, he loaded his equipment onto a military lorry and drove to Stepanakert, reaching the city after dark. Hrayr spent the night at home. He was so exhausted that he didn’t remember falling asleep. In the morning he dressed in civilian clothes. “I dug a hole in the yard in front of our house and buried my uniform,” he told me.

In Stepanakert there was panic. All semblance of authority had disappeared. Thousands of people had converged on the capital from the surrounding villages. People queued at banks to take out their gold. Soldiers burned their uniforms. At the memorial wall for those slain in battle, relatives cut out the portraits of their loved ones to carry away with them. In the vacuum of information, rumours spread of Azerbaijani incursions into the capital.

In Yerevan, I met Gegham Stepanyan, the human-rights ombudsman in Nagorno-Karabakh since 2021. In the midst of the chaos he had tried to record casualties as best he could. When we spoke, his face rigid, as if his anger was kept in check only by the force of his sorrow. I asked him who had made the decision for the general evacuation. Stepanyan turned his palms upward. The question was moot. Over generations, Armenians have developed an instinct for when to fight and when to flee. After three days of negotiation, the Azerbaijanis agreed to allow Armenians through the Lachin corridor without passports. By that stage, many had already packed their cars.

Everyone was consumed with the hunt for petrol. “I was searching all night,” Hayk said. “There were thousands of people on foot roaming the town…I went from petrol station to petrol station. At one, there was a queue of 2,000 people.” Finally he stumbled across a tank with a makeshift hose that still had some fuel remaining. “It was not just a miracle,” he said, “It was something like a rebirth. Because with petrol, you could save your family.”

On September 26th there was an explosion at a fuel depot where a huge crowd had gathered. Estimates suggest 170 people were killed. Anatoly heard the blast and rushed to the morgue. A former emergency responder, he spent the following days helping relatives identify the victims. “It was an inhuman picture,” he told me. Most of the bodies were burnt black and unrecognisable.

The tragedy didn’t slow down the evacuation. Hrayr and Hayk gathered their families and their parents and set off in a convoy of ten cars. The 70km drive took over 24 hours. “We worried all the way,” Hayk told me. “Your brain isn’t working. You are driving one metre and then stopping again.” People cooked on open fires at night, sharing food and precious drops of petrol. The road was littered with abandoned cars, Anatoly waited until most people had left before getting into his car. “I am a patient man,” he said, with half a smile.

Armenia has absorbed the loss and the refugees. Demonstrations against the prime minister, who had been blamed for sacrificing Karabakh, were relatively small. Refugees are being housed and given assistance. Yerevan State University had announced that it would accept students from Stepanakert. But there is still fear of further conflict. The Azerbaijanis are pushing to open a corridor along the Iranian border to link Azerbaijan to Nakhichevan, its own enclave in Armenia. Some fear they will try to attack Armenia itself. Gunfire has been exchanged across the border.

The Armenians who fled Karabakh are in shock. None said they would live under Azeri authority. When I asked Stepanyan, the human-rights ombudsman, what he would do now, he said, “I will try to finalise the lists of people who died, and find out the fate of the missing people. After I have done that I will never, never, never have a public position again.”

A few Karabakh Armenians I talked to spoke of continuing the fight. Hayk told me he believed he would return, “But it will only happen through war. It will be a matter of years. But it will definitely happen again.”

The Yerablur cemetery, where the dead of Karabakh’s wars are buried, stands on a hill outside Yerevan. Black headstones mark the dead from the 1990s; white headstones mark those killed in 2020. I watched a yellow digger scraping out a new section of the hillside. There were already several rows of new graves covered in mounds of fresh flowers. A priest in robes with royal-blue brocade intoned the rites as a rifle salute cracked and a military band played a martial song. Groups of mourners came, one after another, carrying in their arms children, chrysanthemums and portraits of the dead. ■

Wendell Steavenson has reported extensively on the war in Ukraine for 1843 magazine

PHOTOGRAPHS THOMAS DWORZAK

More from 1843 magazine

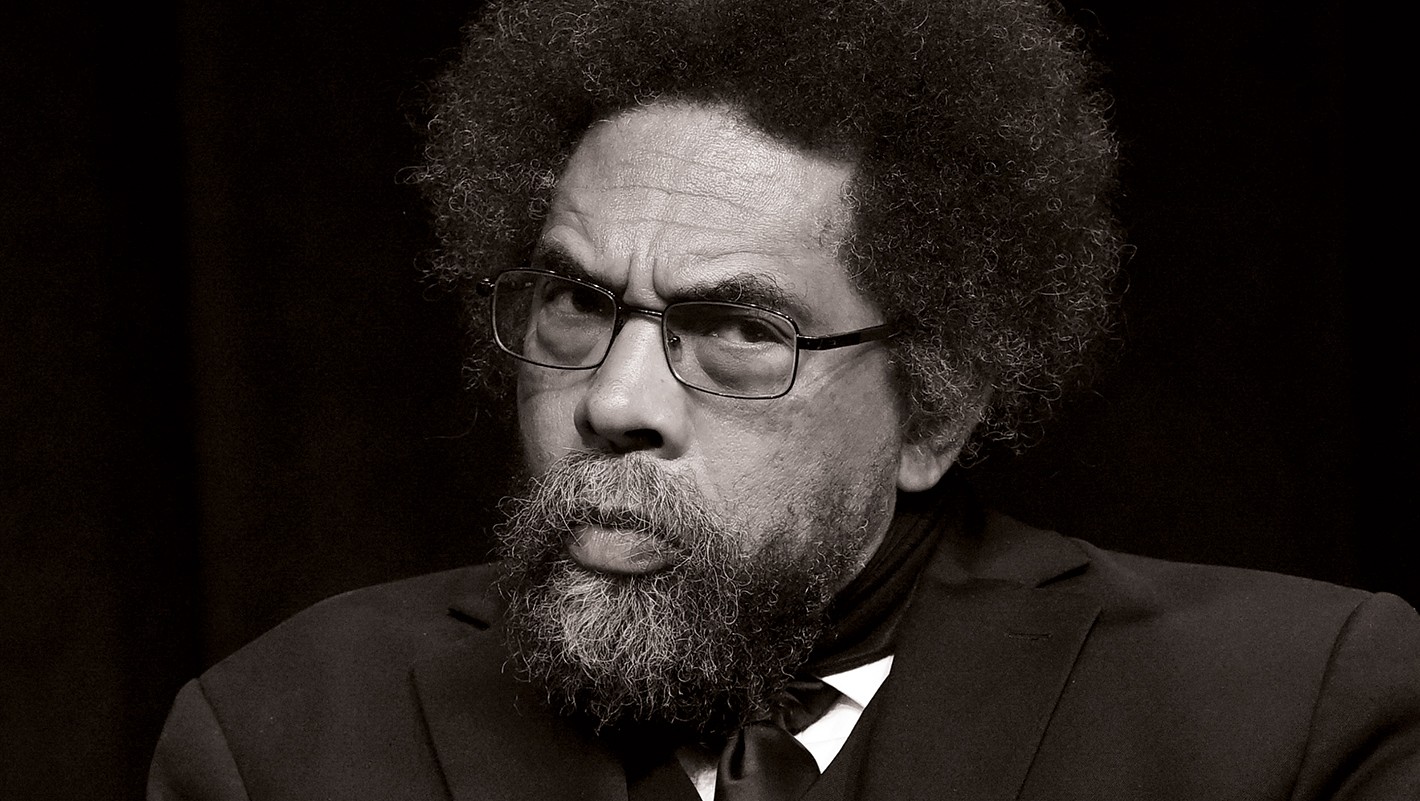

1843 magazine | Cornel West’s quixotic presidential bid holds dangers for Joe Biden

He’s not going to win, but his long record of pro-Palestinian activism might attract left-leaning Dems – if he can get on the ballot

1843 magazine | Afghans fled the Taliban in droves. Now Pakistan wants to send them back

Omid has been living in Pakistan without a formal permit. The police are trying to push him out

1843 magazine | When the New York Times lost its way

America’s media should do more to equip readers to think for themselves