By Dan Halpern

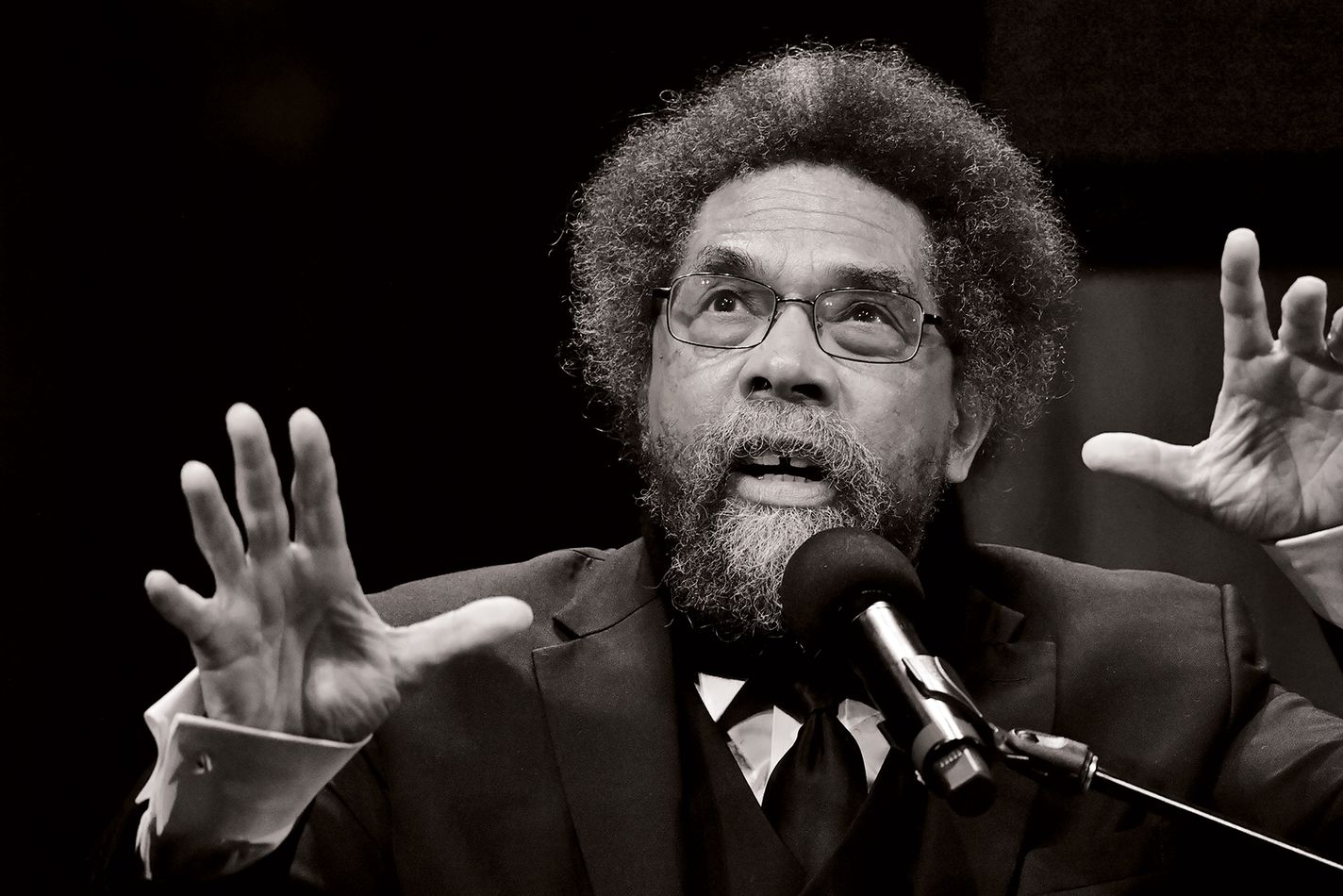

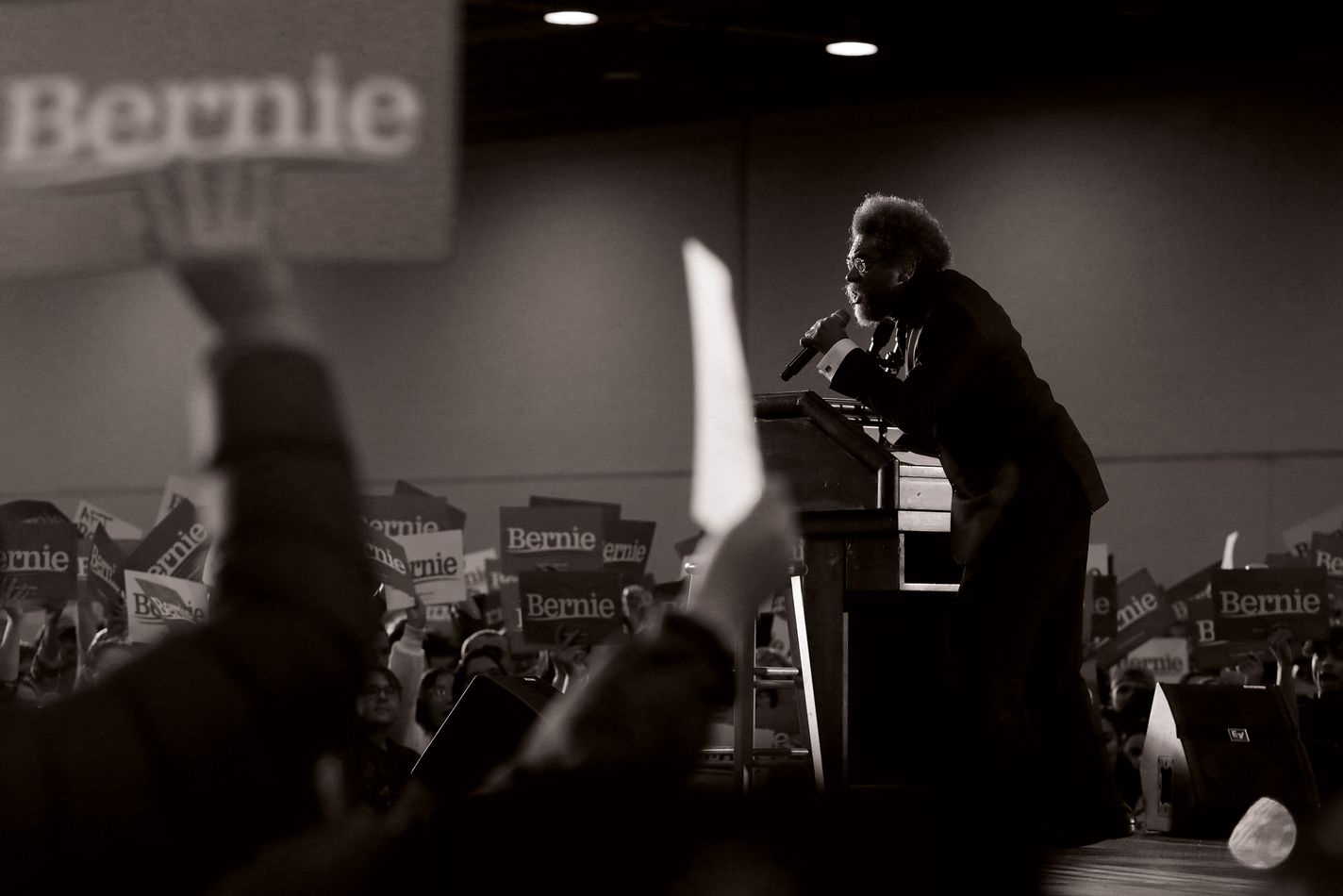

The queue at the Comedy Cellar stretched all the way to the end of the block. The crowd, wrapped up for a December evening in New York, didn’t seem to mind much. They had come to witness a conversation between Cornel West – philosopher, theologian and starry public intellectual, now in the early stages of an independent run for the presidency of the United States – and Norman Finkelstein, an anti-Zionist academic and activist who had once called Israel the “Jewish supremacist state”. West, too, has been a longtime critic of Israel, and, with no end in sight to the invasion of Gaza, the prospect of an evening of revolution and resistance, power and praxis had brought downtown New York City out in droves. The club’s two-drink minimum went largely unheeded.

As the show began, Finkelstein seemed more interested in interviewing West about his campaign for president than in talking about the war. He wanted to know whether West could build on Bernie Sanders’s strong showings in 2016 and 2020 and probed him for the kind of details insiders delight in – the state of his ground game, strategy, messaging.

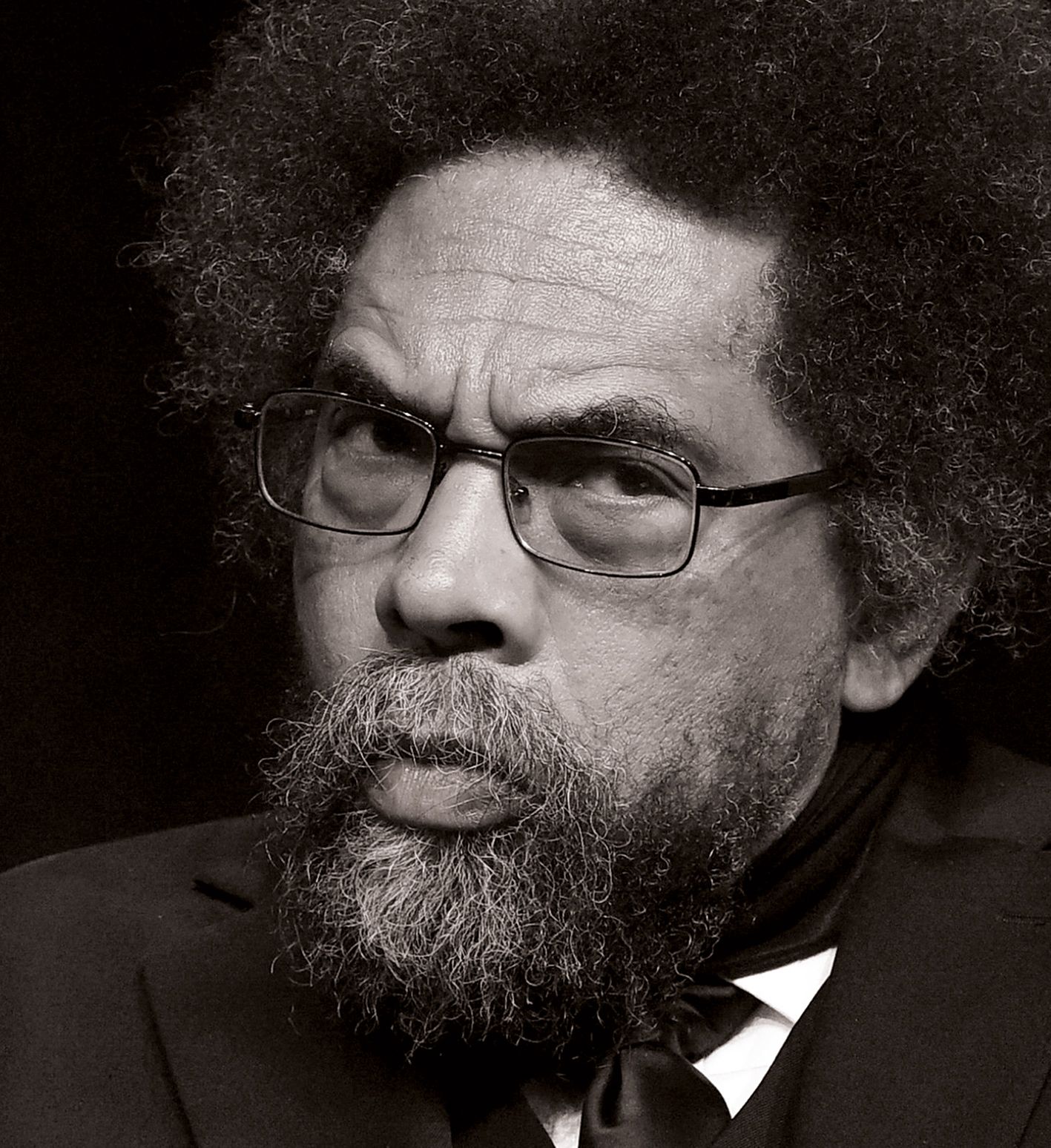

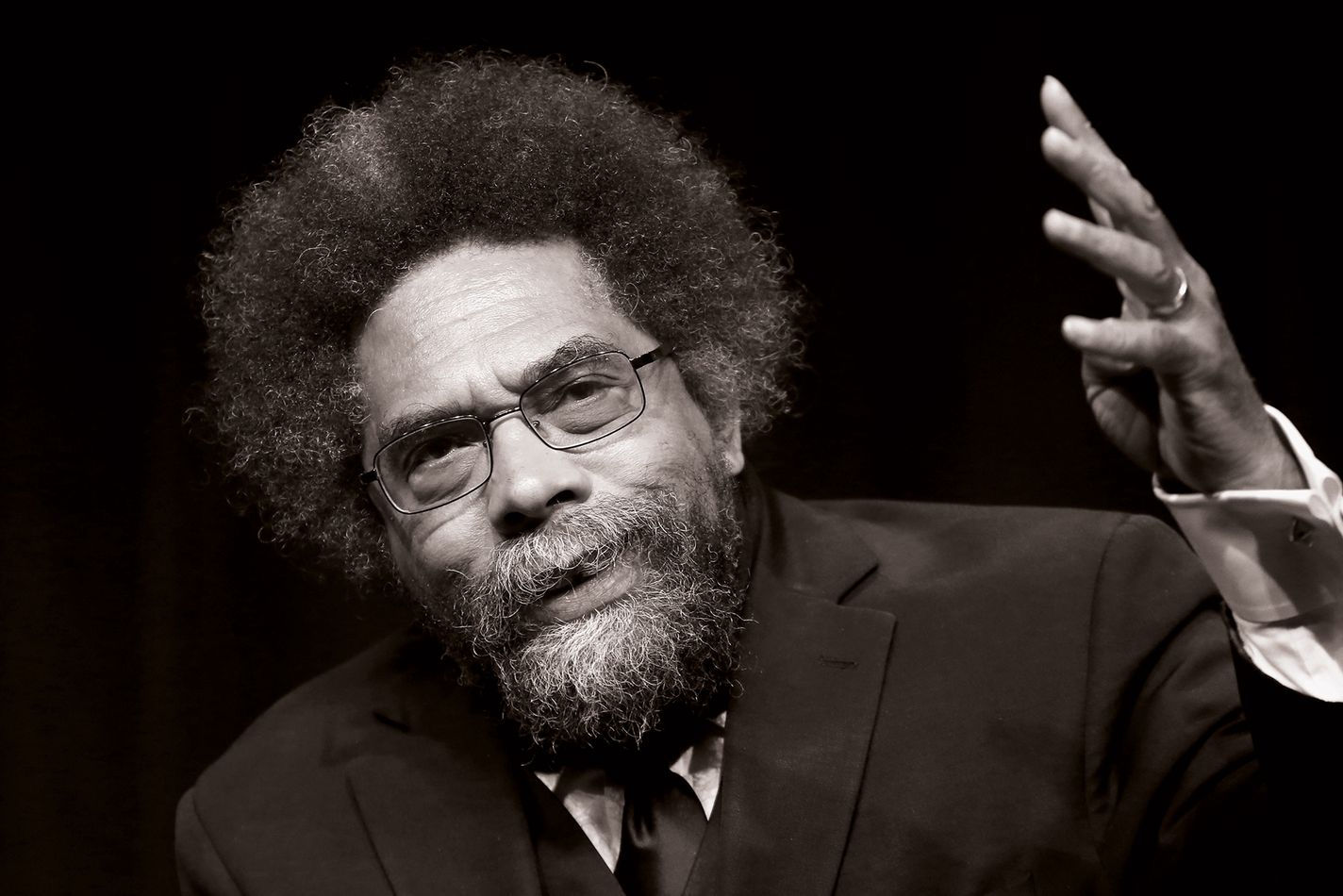

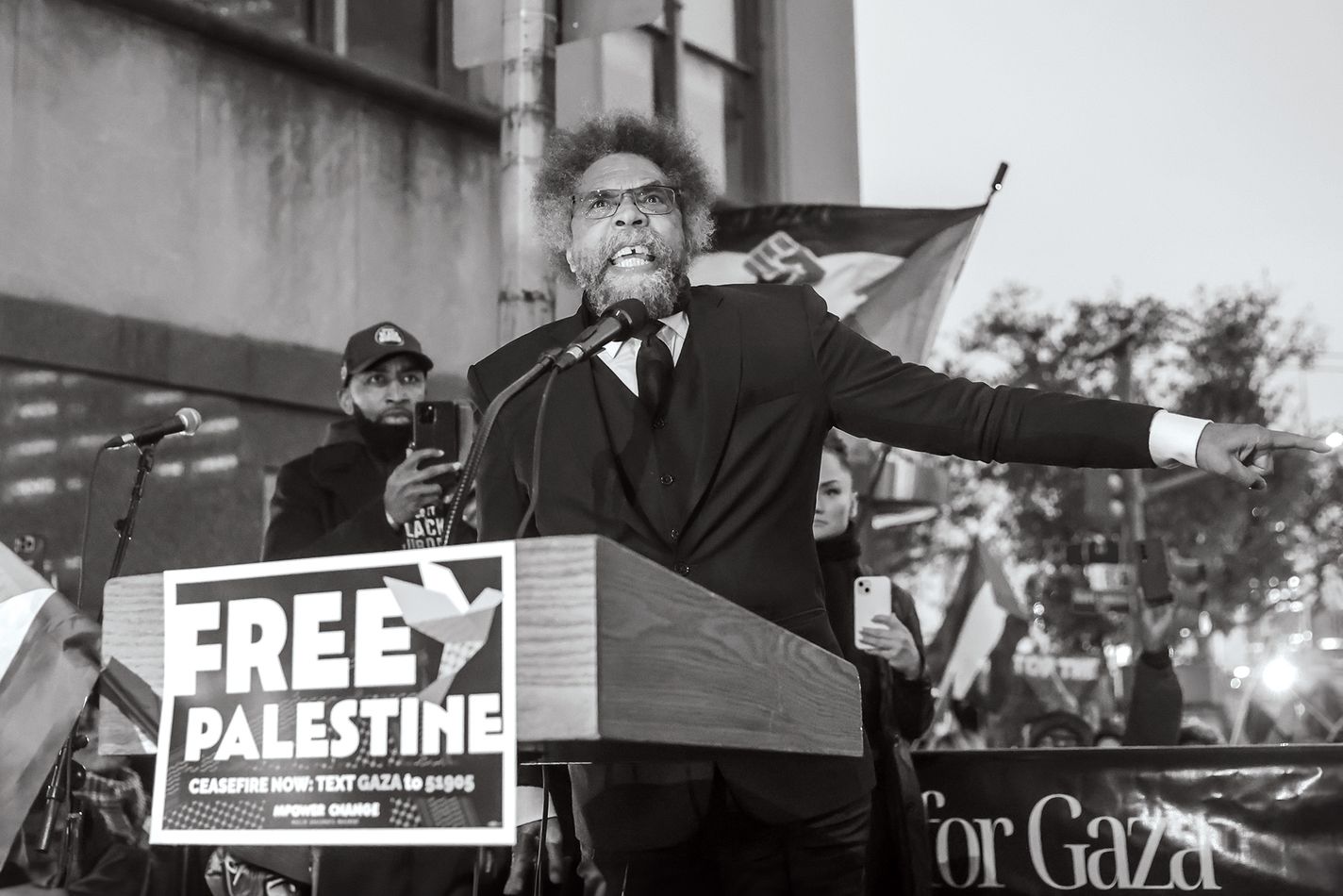

West – dressed in his standard uniform of a black three-piece suit, a white shirt with French cuffs and a scarf – leapt to his feet. He paced up and down the stage, addressing Finkelstein, then the crowd, his index finger propelled like a conductor’s baton, pointing to the sky and then following his thought all the way to the ground. West has the charisma and energy of James Brown, if the Godfather of Soul had gone to graduate school. Finkelstein – tall, pale, possessed of a severe mien and a high, flat voice – wisely chose not to try to compete.

After dispensing with some of the nuts and bolts of campaign tactics, West moved to what he considered to be the heart of the matter: “If you believe as I believe, that most of human history is the history of domination and oppression and exploitation, organised greed, institutional hatred, routinised indifference towards the suffering of vulnerable people, of poor people,” West said, “the question becomes, what do we do in this moment?”

If you’re the Democratic Party, the answer to West would be “anything other than run for president, please”. He has yet to qualify for any state ballots beyond Alaska, and stood at only 2-3% nationally, but it’s a “very important 2-3%”, the pollster John Zogby told me. “His appeal is to young voters, progressive voters and black voters. And every vote he gets is a threat to Joe Biden.” West’s decades-long support for Palestinian rights in particular make him a credible alternative for those on the left of the Democratic Party appalled by the current administration’s diplomatic and military backing of Israel’s campaign in Gaza.

In a December poll in Michigan and in Georgia, two critical states for the president, support for West rose to 6%. If he makes the ballot there, his run could affect the outcome of the election. In 2020, Biden won Michigan by about 150,000 votes; 6% of all votes cast in the state would come to about 325,000. More than two months into the Israel-Hamas war, Biden’s numbers continue to decline, and West is taking advantage of the opportunity. Only a week after the event in Greenwich Village, West was in Dearborn, Michigan, giving the keynote address at an event called “Gaza Endures”, sponsored by state and local organisations including the Michigan chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations and the Detroit chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace.

“From the very beginning this campaign has always viewed itself as a moment within a movement”, West told the Comedy Cellar crowd, “that comes out of a struggle of a people who have been hated chronically for 400 years but produced love warriors for every generation.”

This riff was taken from West’s stump speech, to the extent that he has one: he tends to improvise within the same set of themes, but is always consistent in locating the campaign’s origins within the history of oppression visited upon African-Americans. He switches codes and modes, here exhorting in the style of a Baptist preacher, there explaining in the jargon of the academy. His speech is poetic and plain, high and low, invoking at one moment the language of radical Christianity, at another that of socialism. This is not the way a presidential candidate traditionally speaks, but even more unusual was West’s admission that his campaign might be merely a small step in a longer struggle, as opposed to an inexorable march to electoral victory. No campaign – even one as far outside the mainstream as West’s – is supposed to admit this.

The themes of his campaign are truth, justice and love: pretty good ones, generally speaking, and authentic to a candidate whose essential motivation lay in a deeply felt Christian sense of responsibility to protect the weak and speak for the suffering. It might not be a tightly honed message that would test well in focus groups, but West 2024 wasn’t much about the consultant class. That none of the love warriors in West’s pantheon – thinkers and activists and artists, from W.E.B. Du Bois to Martin Luther King to John Coltrane – had ever been elected to anything didn’t bother him. His job, he said, was simply to push the wheel of justice forward as far as he could push it.

West was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1953, the grandson of a pastor and the great-grandson of sharecroppers and former slaves. His parents, Clifton and Irene, moved the family to Sacramento when he was five. At 17, he went to Harvard, graduating in three years with a degree in Near Eastern languages and civilisations, before doing a PhD in philosophy at Princeton; over the past four decades, he has been on the faculty at Yale, Harvard and Princeton, teaching philosophy, religion and African-American studies, as well as at Union Theological Seminary, where he is now the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Chair of Philosophy & Christian Practice.

His wider fame as a public intellectual dates to the publication, in 1993, of a general-interest book of essays called “Race Matters”, which argued that the problem of race relations in the United States would not be solved by changing the situation of black people, but rather by changing America itself. The book foreshadowed contemporary conversations about structural racism – helping to popularise the notion that discrimination was woven into American culture, society and, perhaps most importantly, economics. “Race Matters” became a surprise bestseller, earning him an invitation to the Clinton White House, and shooting him into the world beyond academia. Since then he has been a friend to senators and presidents from Bill Bradley to Bernie Sanders, Bill Clinton to Barack Obama, though he’s been repeatedly disappointed when some of these figures have embraced Wall Street at home and hawkishness abroad. He has marched, exhorted and organised on behalf of labour unions and for black lives. Beyond politics, he has recorded hip-hop albums, acted in “The Matrix” sequels, and been spoofed on Saturday Night Live.

Not everyone has been impressed by his ubiquity. As his celebrity and political activism increased, his scholarly output decreased and detractors began to suggest that he had been corrupted by fame, reduced to a superficial television talking head. In his memoir, “Brother West: Living and Loving Out Loud”, he describes himself as someone who has been on the move his entire life. He has never stayed attached to any institution for long, flitting back and forth between Harvard and Princeton and Union multiple times. He travels the country for speaking engagements hundreds of times a year – “a bluesman of the mind”, as he puts it, singing for his supper. This lifestyle has, doubtless, taken its toll – or at least, given his detractors grist. West, who is now married to his fifth wife and describes himself as “broke as the Ten Commandments”, reportedly owes the IRS almost half a million dollars as well as almost $50,000 in unpaid child support. Despite being a scholar known the world over, he was twice denied tenure by Harvard despite having served as a University Professor, the institution’s most prestigious title.

West had announced his intention to run for president in June. The rollout was not a smooth one. He was briefly attached to the People’s Party, a progressive political organisation that wanted to be “free of corporate money and influence”, then moved to the Green Party before finally deciding to go it alone as an independent. His unlikely platform calls for, among other things, a $27-an-hour minimum wage, nationalising the fossil-fuel industry, and cancelling all student debt. After that, he gets to the really ambitious stuff for which he has less of a plan: abolish poverty, end the global patriarchy and dismantle the American empire.

Historically, the major parties have ignored candidacies like West’s, as has, in large part, the press, who tend to treat such efforts as curiosities. But as next year’s election draws closer, visions of a Trump dictatorship are driving Democrats to hysteria. They are haunted by Jill Stein’s role in Michigan in 2016 and Ralph Nader’s in Florida in 2000, which denied their candidates victory in the electoral college. The party faithful – and to a great extent the less faithful – have lined up to say that West’s campaign is a bad idea. That the best, and worst, West can do is help re-elect Donald Trump.

Since announcing, West had been accused of all manner of unsavoury motivations: ego, resentment, greed. Why was he doing this? Did he possibly think he could win? What right had he to buzz around the edges of an incipient apocalyptic battle between Good and Evil? West’s response, to me and in his speeches to crowds, was that he felt he had been called to join those freedom fighters he admired. The choice between Biden and Trump was no choice at all for the poor and working people of the country, he said. Certainly, no choice for those he considered oppressed around the world.

This calling grew out of a lifetime of reading and thinking, from Plato to Marx, Kierkegaard to Chekhov, Hume to Dewey. But its real foundation, West wanted his audiences to understand, was the Shiloh Baptist Church in Sacramento. There, he had received and accepted the message that he says God asks us of all, to testify to what we see, to bear witness to suffering and degradation, and never to be silent, no matter what powerful forces try to silence us.

West has called Donald Trump a “fascist catastrophe” and Joe Biden a “neoliberal disaster” – a disaster may be better than a catastrophe, he said, but we deserve something better. Press commentary that Trump might be preparing to establish a dictatorship, he felt, was insufficient to justify sticking to the two-party script. I asked West if he had a novel answer to the accusation that he was endangering democracy by courting votes Biden might have otherwise counted as his own.

“Biden’s so tied to organised greed; so is Trump,” West said. “Biden’s so tied to organised militarism; so is Trump. Biden’s so tied to organised Manichean perspectives; so is Trump. So there are structural similarities that need to be radically called into question.”

West acknowledged that Biden was marginally preferable to Trump on a number of issues, but that wasn’t enough to convince him to back down. In his mind, reluctant compromise would not solve the problem of Trumpism. “You’ve got to present the people who support fascism with a substantive alternative, or the candidate who’s tied to just the strategic and the tactical will merely postpone fascism,” he told me. “Trumpism will outlast Trump. Fascism will, sooner or later, take over, because the people don’t have an alternative. And Biden simply is not an alternative.”

The day before the event in New York, I’d joined the West team in Omaha, Nebraska, for a series of campaign events. From the airport, West was whisked to lunch with a group of farmers gathered to educate him on their concerns. Seated around tables in a former Lutheran church were some 15 or so farmers – mostly young, a mix of white and black. “The next generation of farmers is in trouble,” said Graham Christensen, a fifth-generation Nebraska farmer and organiser. “Everything is top down, totally controlled.”

West is an intent and active listener, and he was mostly quiet, occasionally leaping up to hug someone. “Corporate America wants you to think there’s no alternative,” West finally said, when everyone in the room had had a chance to speak. “I tell everybody that the slaveholder said there was no alternative. They tell me everything is frozen as it is. Some of us are going to bear witness, no matter what. I’m not naive. It’s difficult. But when the imperial powers in Africa said, there’s no alternative, someone said, watch this! When they said there’s no alternative in 1860, we said, watch this! When the power in Palestine says there’s no alternative, we say, watch this! Watch this! Watch this!”

After a quick stop at the Aframerican Bookstore – posing for photos, more hugs – the next gig was North High School, a behemoth of a building where West addressed about 100 students, most of them black. There have probably been presidential candidates who spoke to a crowd for almost an hour without mentioning that they’re running, but I’ve never seen one. “I have heard that you plan on becoming the president of the United States,” one student finally asked, almost 40 minutes into a question-and-answer period. “If that should happen, what are your socio-economic plans for this country?”

“I didn’t really want to talk about the campaign in the context of school,” West told her. “A high school is a place of education.”

“I had two questions,”said another student, a teenage boy. “First, what is your opinion of Donald Trump?” The crowd laughed.

“I’ll use two words,” West said. “Bonafide gangster.” The crowd laughed harder.

“My second question was, do you think this generation is screwed,” said the boy, “or not.”

“How would you define screwed, though?” West asked.

“Like – too far gone, there’s no hope.”

“Oh no, no, no, no, no, no, no,” West said. “Your generation has certain catastrophes coming at it: ecological, possible nuclear, economic, social. But no, your generation is no way screwed, not at all. I’m looking at folk in this room right now. How many in this room have courage, raise your hand! How many in this room have hope, raise your hand! How many have love, raise your hand! Oh, shoot, we in good shape!”

After the high-school event, West made a quick visit to a coal-fired power plant, which he was calling to have shut down. Then he was off for a brief pilgrimage to the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation, where he exclaimed joyfully at the objects and documents on display.

From there he headed to a rally. Christensen, the farmer from lunch, was in attendance. “I liked him,” he told me. “The same old thing isn’t working.

As West took the stage and began speaking to an audience of about 100 people, I was struck at just how skilled he was at rousing the crowd. Truth, justice and love might seem like abstractions in an age of wedge issues, but when West proclaimed, “Like we used to say at Shiloh Baptist Church: we just trying to love our crooked neighbour with our crooked heart,” the number of head nods and cheers suggested otherwise. West can speak from a position of righteous fury, but his insistence on love as a response to catastrophe is a constant. He insists he loves everyone, including those who disagree with him, whose opinions he actively seeks. These include the billionaire Republican donor Harlan Crow, whom West considers a friend. (A minor scandal occurred when Crow donated the maximum allowable amount to West’s campaign. West, under pressure from the press and the left, ultimately returned the money.)

“At the moment it looks like it’s David versus Goliath, but I am always in solidarity with the Davids of the world!” West told the audience. By now he was really hitting his stride, and everyone was mesmerised. “The Goliaths always appear as if they’re so MIGHT-TY…as if time is not a taker!”

“Tell it!” someone shouted from the crowd.

“The two-party system is more and more an impediment! If all we can do is come up with Trump leading us to a second civil war and Biden leading toward a third world war, we are in a world of trouble!”

“That’s right!” called somebody else.

Cornel West had come to witness. Whether his testimony would have any effect on the election is up to forces beyond him. ■

Dan Halpern is a feature writer for 1843 magazine.

PHOTOGRAPHS: GETTY

More from 1843 magazine

1843 magazine | Nagorno-Karabakh, the republic that disappeared overnight

It had been clinging on to its self-proclaimed status in the face of Azerbaijan’s aggression. Then, over a week, the entire population fled

1843 magazine | Afghans fled the Taliban in droves. Now Pakistan wants to send them back

Omid has been living in Pakistan without a formal permit. The police are trying to push him out

1843 magazine | When the New York Times lost its way

America’s media should do more to equip readers to think for themselves