Frequently asked questions

Why does The Economist call itself a newspaper?

When James Wilson published the prospectus for The Economist, a new periodical he planned to launch, he described it as “a weekly paper, to be published every Saturday”. To modern eyes the 19th-century black-and-white incarnation of The Economist is clearly a newspaper, and it looked very similar until the middle of the 20th century. The red logo appeared for the first time in 1959, the first colour cover in 1971, and it was only in 2001 that full colour was introduced on all inside pages. By the time the transformation from newspaper to magazine format had been completed, the habit of referring to ourselves as “this newspaper” had stuck.

Is The Economist left- or right-wing?

Neither. The Economist’s starting-point is that government should remove power and wealth from individuals only when it has an excellent reason to do so. When The Economist opines on new ideas and policies, it does so on the basis of their merits, not of who supports or opposes them. The result is a position that is neither right nor left but a blend of the two, drawing on the classical liberalism of the 19th century and coming from what we like to call the radical centre.

Where is your head office?

The modern, global version of The Economist was created in “the tower”, as journalists refer to the tallest of the three brutalist concrete buildings that make up the Smithson Plaza (formerly The Economist Plaza) in St James’s Street. Commissioned by The Economist and designed by Alison and Peter Smithson, the tower was our home from 1964 until the summer of 2017, when we moved into the Adelphi, a 1930s art-deco office block on the Embankment.

How has your logo evolved?

The corporate logotype of The Economist has evolved from the gothic lettering used on the cover of the first issue, published in 1843, to the box device designed in 1959 by Reynolds Stone, a British engraver and typographer. It now incorporates a font from The Economist Typefamily, a typeface created specifically for our use.

Editorial philosophy

Editorial practices

The Economist has been published since September 1843 to take part “in a severe contest between intelligence, which presses forward, and an unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our progress”. This mission continues to guide our coverage: we publish it every week in the newspaper.

Our readers expect us to keep them well informed about the world. So each week in print and each day online we provide a carefully selected global mix of stories. Our news priorities are reflected in the sections that we include in the paper every week: these are both geographical (Britain, Europe, the United States, the Americas, China, Asia, Middle East and Africa, International) and thematic (Business, Finance and economics, Science and technology, Books and arts). By systematically sifting news in these categories we aim to ensure that readers miss nothing important. In addition, through leaders, briefings and special reports we strive to identify ideas and trends that will shape global developments—and keep us and our readers engaged in the “severe contest”. This approach underpins all our editorial output, across digital outputs and sister publications. Our stories offer a distinctive blend of news, based on facts, and analysis, incorporating The Economist’s perspective.

We do not attach ourselves to any political party. Our public agenda is liberal in the classical sense. We have supported free trade ever since our foundation in 1843 when we opposed Britain’s corn laws, which sought to keep the price of grain high by limiting imports. We have continued to advocate bold policies in favour of individual freedoms, such as same-sex marriage, assisted dying and legalisation of drugs, regardless of whether they are politically popular, in the belief that the force of argument will eventually prevail.

Ethics

The Economist strives for the highest ethical standards. Our approach falls under two headings:

Core principles

We should be honest, fair and fearless in gathering, reporting and interpreting information.

We are accountable to our readers, listeners, viewers and each other.

We steadfastly uphold our editorial independence.

We use objective data and research to inform our journalism. All our editorial output is fact-checked.

We apply classical liberal values transparently in our reporting and analysis.

We are transparent about conflicts of interest (see below). As an anonymous newspaper, we have to be especially beyond reproach.

Conflicts of interest

The editor-in-chief sets clear rules on conflicts of interest. These are reviewed and re-circulated periodically. Journalists know that the penalty for non-observance of the rules can be dismissal.

Our journalists should disclose any possible conflicts of interest, such as beneficial holdings, directorships and freelance engagements. The editor-in-chief keeps a registry of journalists’ interests, and updates it annually.

Any journalist wishing to accept a trip offered by a government, company or other entity must obtain approval by a senior editor. Such trips should be rare—for example, when a trip cannot be taken at our own expense, such as travel into a warzone.

Journalists arriving at The Economist from a partisan political job will not be allowed to write for some time about policy or politics in the country in which they held that job. Journalists covering politics or policy cannot contribute money or help to a political party or organisation in the country they are working in.

Facilitation payments to expedite or secure a government action are not acceptable.

Author anonymity

Most newspapers and magazines use bylines to identify the journalists who write their articles. The Economist, however, does not. Its articles lack bylines and its journalists remain anonymous. Why?

Part of the answer is that The Economist is maintaining a historical tradition that other publications have abandoned. Leaders are often unsigned in newspapers, but everywhere else there has been rampant byline inflation (to the extent that some papers run picture bylines on ordinary news stories). Historically, many publications printed articles without bylines or under pseudonyms to give individual writers the freedom to assume different voices and to enable early newspapers to give the impression that their editorial teams were larger than they really were. The first few issues of The Economist were, in fact, written almost entirely by James Wilson, the founding editor, though he wrote in the first-person plural.

But having started off as a way for one person to give the impression of being many, anonymity has since come to serve the opposite function at The Economist: it allows many writers to speak with a collective voice. Leaders are discussed and debated each week in meetings that are open to all members of the editorial staff. Journalists often co-operate on articles. And some articles are heavily edited. Accordingly, articles are often the work of The Economist’s hive mind, rather than of a single author. The main reason for anonymity, however, is a belief that what is written is more important than who writes it. In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, our editor from 1938 to 1956, anonymity keeps the editor “not the master but the servant of something far greater than himself…it gives to the paper an astonishing momentum of thought and principle.” The notable exception to The Economist’s no-byline rule, at least in the weekly issue, is special reports, the collections of articles on a single topic that appear in the newspaper every month or so. These are almost always written by a single author whose name appears once, in the rubric of the opening article. By tradition, retiring editors write a valedictory editorial which is also signed. But print articles are otherwise anonymous.

Different rules apply in the digital realm. We identify our journalists when they appear in our audio and video output. And many of them tweet under their own names. The internet has caused our no-byline policy to fray a little around the edges, but the lack of bylines remains central to our identity and a distinctive part of our brand.

Unnamed sources

We make use of unnamed sources and conversations on background because they can be more informative. We may withhold the name of a source who talks to us on the record, if that individual might be put in danger or legal jeopardy if their name is revealed or if we deem it otherwise unnecessary to name them. We strive to describe unnamed sources with as much detail as we think readers need to assess their credibility.

Fact-checking and corrections

Every single article we publish is checked for accuracy and credibility. We have a dedicated Research department to support this task.

Authors are expected to write with fact-checking in mind, and should be ready to provide source material and to discuss and respond to questions.

Our Research department works on edited copy as close to the final version as deadlines allow. We check against original sources that we believe to be reliable; for items that cannot be verified directly we form a view based on other credible information.

We also consider whether the context and presentation of the facts are fair.

We discuss queries with the author or editor. All queries must be resolved before a story is published. The final say on any matter rests with the relevant editor.

We’re not perfect, and occasionally we make an error. We aim to acknowledge serious factual errors and correct such mistakes quickly, clearly and appropriately. Online, published corrections should note what was wrong, what was put right and when. In print, we may publish a correction in the same section in a future issue of the newspaper. Readers who wish to bring potential errors to our attention are encouraged to email us.

Diversity

The Economist welcomes applications from people of all backgrounds, regardless of any characteristics—visible or invisible—or beliefs. We are convinced that drawing talent from a broad pool makes for better journalism and a better paper, and that breadth of perspectives and experiences leads to richer debate. Echo chambers of the like-minded do not. We are therefore actively and continually looking for new colleagues who can enrich our newsroom and help us produce mind-stretching journalism.

We have substantially intensified our efforts to attract candidates from a wider range of backgrounds. We have broadened the range of channels through which positions are advertised. We work closely with specialist organisations to reach applicants from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds. Our selection process is designed to remove any unnecessary barriers to talented people. We require diversity in both gender and race/ethnicity in all shortlists.

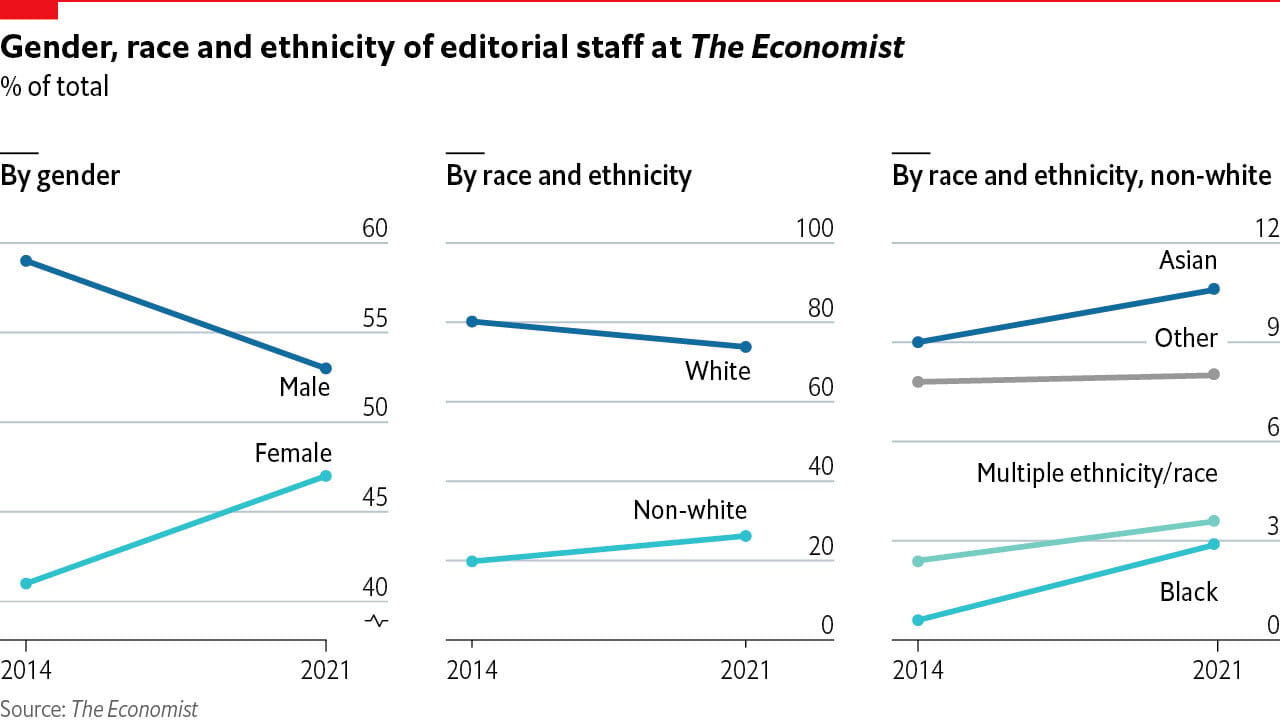

To help hold ourselves accountable to our commitment to diversity, we have since 2017 published data on the composition of our editorial department by gender, and race and ethnicity. We realise that these metrics do not capture all measures of diversity, nor indeed all the forms of diversity we care about. As a British newspaper, our home city is London, where we hire and train most of our editorial staff, drawing on an international pool of talent.

Our idea of a good workplace is one where all employees feel at ease, are able to develop and grow, and get the flexibility and support that they need for a healthy work-life balance. We offer, and actively encourage, a range of ongoing development and training opportunities for all members of staff.

Ownership

The Economist has been editorially independent since it was founded in September 1843 to take part “in a severe contest between intelligence, which presses forward, and an unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our progress”.

The share capital of The Economist Newspaper Limited, The Economist Group’s parent company, is divided into ordinary shares, “A” special shares, “B” special shares and trust shares. The company is private and none of the shares is listed. Its articles of association also state that no individual or company can own or control more than 50% of its total share capital, and that no single shareholder may exercise more than 20% of voting rights exercised at a general meeting of the company.

Ordinary shares are principally held by employees, past employees, founding members of the company and, more recently, by Exor NV. The ordinary shareholders are not entitled to participate in the appointment of directors, but in most other respects rank equally with the other shareholders. The transfer of ordinary shares must be approved by the Board of directors.

The “A” special shares are held by individual shareholders including the Cadbury, Rothschild, Schroder and other family interests as well as a number of staff and former staff.

The “B” special shares are all held by Exor which holds 43.4% of the total share capital of the company excluding the trust shares. Exor purchased the majority of its shareholding from Pearson plc in October 2015.

The trust shares are held by trustees, whose consent is needed for certain corporate activities, including the transfer of “A” special and “B” special shares. The rights attaching to the trust shares provide for the continued independence of the ownership of the company and the editorial independence of The Economist. Apart from these rights, they do not include the right to vote, receive dividends or have any other economic interest in the company. The appointments of the editor of The Economist and of the chairman of the company are subject to the approval of the trustees.

The general management of the business of the company is under the control of the Board of directors. There are 13 seats allowable on the Board, seven of which may be appointed by holders of the “A” special shares and six by the holders of the “B” special shares.

Governance

The Economist Group is editorially independent and free of partisan bias, state control or outside influence of any kind. Today this autonomy is among our most fiercely upheld attributes.

You can read more about our guiding principles, ownership, board of directors and trustees on The Economist Group’s website.