The world must try to break a vicious cycle of insecurity

The fragility of the Western coalition is a crucial weakness

By Patrick Foulis

AS 2023 drew to a close, wars were raging in Africa, Israel and Gaza, and Ukraine. These crises are explosive in their own right. Combine them with a presidential race in America and 2024 promises to be a make-or-break year for the post-1945 world order.

The 2020s were destined to be dangerous. The West’s share of world GDP has fallen towards 50% for the first time since the 19th century. Countries such as India and Turkey believe the global institutions created after 1945 do not reflect their concerns. China and Russia want to go further and subvert this system. Though America’s economy is still pre-eminent, its unipolar moment has ended. Allies in Europe and Japan are in relative economic decline. There is tepid support among the middle class for America’s global role, and an isolationist tilt in the Republican Party.

At the start of 2023 America was busy adapting to this reality, implementing the Biden administration’s foreign policy. The idea was to be a more selective, even selfish, superpower. Prioritisation had meant quitting Afghanistan and shifting resources to Asia to counter China. Alliances were rejuvenated in the Pacific and in Europe, where NATO was expanded and Ukraine kept afloat. Energy and tech embargoes were used to weaken adversaries, at little cost to the West. Domestic industrial subsidies, though inefficient, were potent: in mid-2023 American factory construction hit its highest rate since the 1950s.

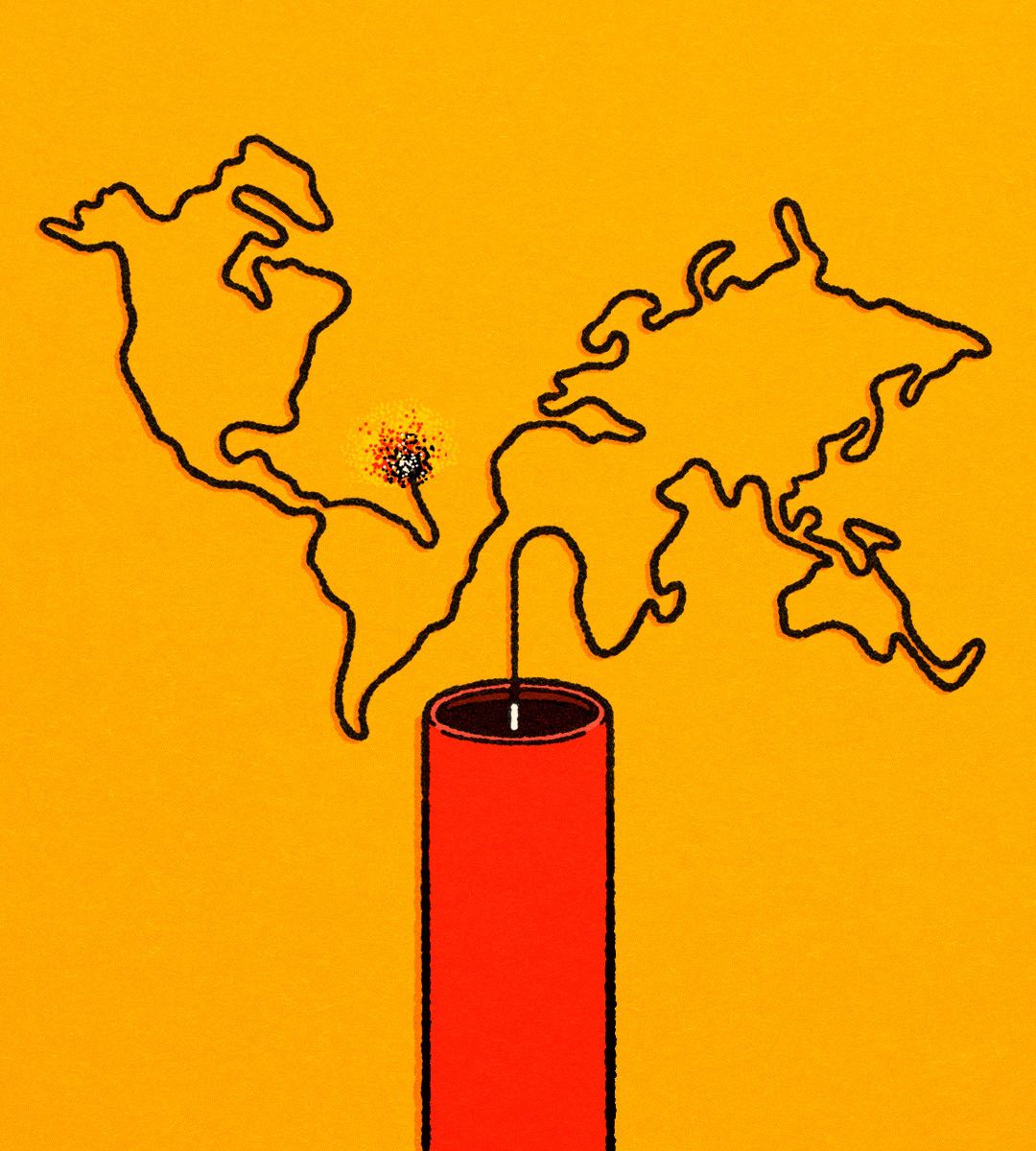

By some yardsticks—oil and grain prices, Western combat casualties—geopolitical risk is tolerable. Yet the new dynamic is one of instability. In the 1990s many countries aspired to a self-reinforcing cycle of freedom, market economics and rules-based globalisation. Now there is an unpredictable cycle of populism, interventionist economics and transactional globalisation. As a result, three threats loom in 2024.

First, there is a growing zone of impunity where neither global powers nor global institutions tread. You can walk 6,000km from the Red Sea to the Atlantic through six African countries that have faced coups in the past 36 months. Azerbaijan has just fought a war against Armenia involving ethnic cleansing, without much blowback. Iran’s proxies thrive in failing states across the Middle East. In 2024 this zone of impunity could expand further across Africa and Russia’s flanks.

Second, a trio of trouble is emerging featuring China, Iran and Russia. They have much less in common than Western allies do, and China is far larger and more integrated into the world economy than the others. But their interests intersect: all want to undermine American legitimacy and to evade actual or potential sanctions. China buys Russian and Iranian oil. None has condemned Hamas or the invasion of Ukraine. Their collaboration is likely to expand into tech. China is pioneering ways to bypass Western finance: half of its trade is now in yuan. Iran exports drones to Russia; China and Russia collaborate on nuclear-warning systems and patrols in the Pacific. In 2024 the world will learn how far this nascent club might go.

The final threat is the fragility of the Western coalition. The response to Ukraine’s invasion was exhilarating: America and Europe united, public opinion was supportive and the principles of the 1945 order were defended, even if non-Western countries were not fully onboard. Now, with a military stalemate, cracks are showing. In America, Republicans are divided over funding for Ukraine. Israel’s invasion of Gaza is even more divisive: it has split the EU and America, which has vetoed a UN ceasefire resolution, fuelling claims of double standards and Western illegitimacy. Other crises could expose more splits: would Europe join America in fighting to defend Taiwan?

How these threats play out in 2024 partly depends on the performance of the West’s autocratic competitors. Just as the very different regimes of China, Iran and Russia share some interests, they have some similar vulnerabilities. All face economic difficulties and rely on intensifying repression. Vladimir Putin faced a mutiny in 2023; Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is 84 and has no clear successor; Xi Jinping relies on purges. All this could sap their vitality and their claim to have a rival model that others should emulate.

But America’s election is key. An isolationist president would not drop treaties overnight but will be tested quickly: think of China “inspecting” Taiwanese ships or Russia “reinterpreting” borders. If America’s commitment falters, Europe will soldier on in Ukraine but will struggle to provide funding or military muscle. Asian allies will placate China and bolster their defences. Middle powers such as South Korea and Saudi Arabia may seek nuclear weapons.

If America elects an internationalist at the end of 2024, much of the world will breathe a sigh of relief. But America faces a long slog to stabilise and then renew a system of international trade and security. The to-do list includes European enlargement; deepening co-operation with India; and a two-state solution between Israel and the Palestinians. Perhaps one day historians will talk of the post-2025 order. ■

Patrick Foulis, Foreign editor, The Economist

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “Multipolar disorder”