Generative AI holds much promise for businesses

Just don’t expect its overnight adoption

By Rachana Shanbhogue

When Chatgpt was first launched at the end of 2022 it quickly became a sensation. Within two months 100m users were posing all sorts of entertaining queries (“Write me a rap song using references to SpongeBob SquarePants”). The number of people Googling “artificial intelligence” surged, and the mania set off investors’ enthusiasm for all manner of AI projects. Yet the real promise, these investors and entrepreneurs are betting, lies with its use in business. Here, too, it could be more rapidly adopted than past innovations. But that does not mean it will happen overnight.

The potential is exciting. According to McKinsey, a consultancy, three-quarters of the business uses of generative ai will fall into four areas: customer operations, marketing and sales, software engineering, and research and development. Navigating a complex tax code or summarising a legal document could become a breeze. Type in the right prompt and a first draft of marketing copy could magically appear. Already many coders rely on Copilot, a coding tool from Microsoft, to help them write software. Studies show that professional workers with below-average performance tend to experience the most benefit from using generative ai, promising a big increase in output for firms.

Helpfully, too, many generative AI tools will be easier to access than previous technologies. This is not like the advent of personal computers or smartphones, where employers needed to buy lots of hardware, or even e-commerce, where retailers needed to set up physical infrastructure before they could open an online storefront. Many businesses may find that they can work with AI specialists to design bespoke tools. And firms such as Microsoft and Google are embedding generative ai into their office software, meaning that anyone opening up a document or a spreadsheet will soon be able to make use of the tools.

Many of the largest companies are already experimenting. Morgan Stanley, a bank, is using AI to build a tool to help wealth managers. Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical firm, has struck a deal with a startup that runs “autonomous labs” to identify promising molecules, which the drugmaker will then develop, test and commercialise. Around 5% of vacancies posted by America’s big banks between 2020 and June 2023 cited AI in the job description, and around 8% of patents registered by big tech firms in 2020-22 were AI-related.

Yet not all businesses will be enthusiastic adopters. Outside the tech world, only a third of global managers tell McKinsey they are regularly using generative AI for work; about half have tried the technology but have decided not to use it, and about a fifth have had no exposure to it all. AI adopters, in short, are outnumbered two-to-one by the wary and the reluctant.

Start with the wary. Some businesses are taking a cautious approach, since much about the technology still needs ironing out. Chatbots are prone to “hallucinations”, or making up things that sound dangerously plausible. And writers, artists, photographers and publishers are challenging AI models’ use of their data in court. Some businesses are wary of being exposed to legal risk by making use of the models, or the reputational risk of taking hallucinations seriously. JPMorgan Chase, a bank, has banned the use of ChatGPT, though it is experimenting with AI in other areas.

Other businesses are reluctant to dip their toe in the water at all. Differences in behaviour between firms at the productivity frontier and those that are less productive are not unusual. Lags in technology adoption can be long. Even though the internet began to be used by companies in the early 1990s, for instance, it was not until the late 2000s that even two-thirds of businesses in America had a website. Many firms have outdated systems—think of the Japanese bank that still uses COBOL—which can make adopting cutting-edge technology a tall order. Managers in the public sector, or in heavily regulated industries such as utilities, may feel little impulse to innovate. Those sectors make up a sizeable chunk of economies: in America they collectively account for a quarter of GDP.

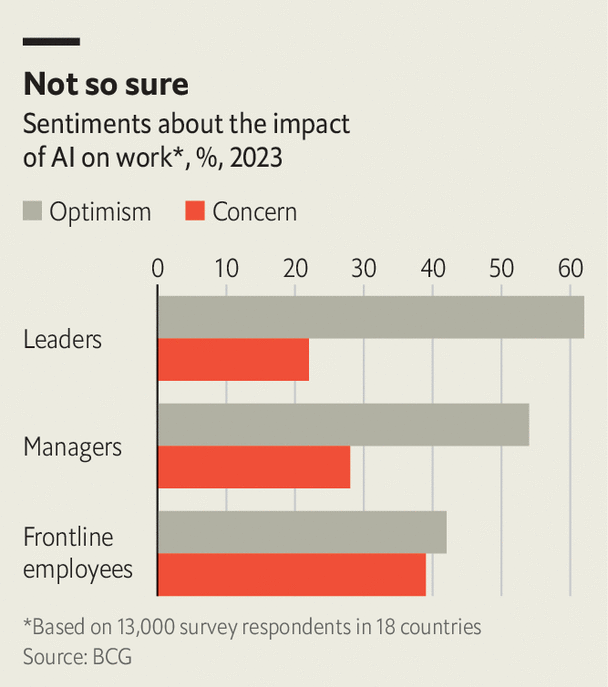

Reluctance can also stem from workers. Although the technology promises to do away with drudgery, some people worry that it may ultimately replace them. A survey by BCG, a consultancy, finds that front-line workers are more likely to be concerned, and less likely to be optimistic, about generative ai than managers or leaders are. In some cases, unions may act to slow the adoption of the technology; some may go as far as the writers’ guild in Hollywood, which was on strike for much of 2023, in part because of concerns about AI’s impact on jobs.

How then should the AI-curious boss think about the technology? It helps to make a clear-headed assessment of the gains to be had, and the costs of using a still new and risky technology, before deciding whether to be an enthusiastic adopter, or a wary or reluctant one. Most important of all, your workers need to be on board. So pay attention to their fears—and convince them of the joys of experimentation. ■

Rachana Shanbhogue, Business affairs editor, The Economist

Explore more

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “The adoption decision”