Ethiopia’s gambit for a port is unsettling a volatile region

Abiy Ahmed is doing a deal for a stretch of Somaliland’s coast

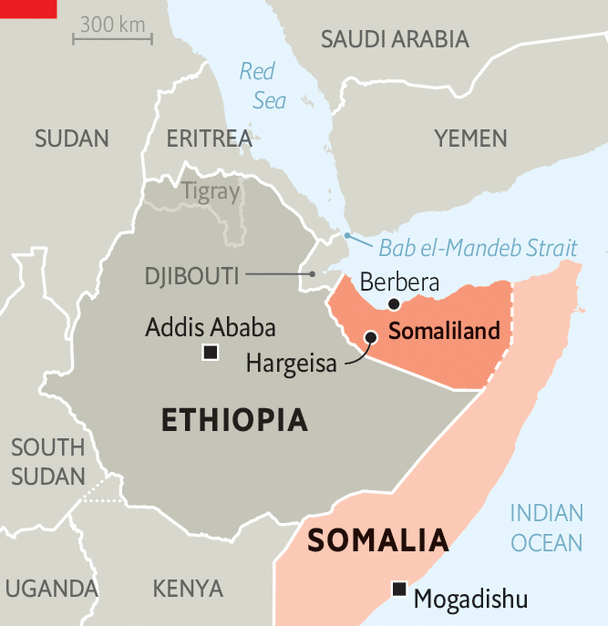

GEOPOLITICS IN THE Horn of Africa are off already to a combustible start in the new year. On January 1st, Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s prime minister, and Muse Bihi Abdi, his counterpart in the would-be state of Somaliland next door, delivered a surprise announcement. At a joint press conference in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, they revealed that landlocked Ethiopia is to lease a naval port and a 20km stretch of Red Sea coastline in the breakaway Somali province. In exchange, Somaliland is to receive shares in Ethiopian Airlines, Africa’s biggest carrier, and—much more significantly—possibly official diplomatic recognition by the Ethiopian government. This would make Ethiopia the first country to formally recognise the former British colony, which declared independence from the rest of Somalia more than three decades ago.

The memorandum of understanding signed by the two leaders has thrown an already volatile part of the world into even greater uncertainty. Authorities in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, have reacted furiously to the news that Ethiopia is willing to break with the African Union’s long-standing policy against redrawing the continental map. “Abiy is messing things up in Somalia,” complains an advisor to Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, Somalia’s president. Just three days earlier Mr Mohamud and Mr Abdi had inked an agreement, mediated by the president of neighbouring Djibouti, to resume talks over Somaliland’s disputed constitutional status. That deal is now in tatters. Following an emergency cabinet meeting on January 2nd, Somalia declared the new agreement “null and void” and recalled its ambassador from Addis Ababa. Urging Abiy to reconsider, Mr Mohamud said the deal would serve only to fuel support for al-Shabab, the al-Qaeda-linked jihadist group which controls much of the countryside and first emerged partly in response to Ethiopia’s invasion of Somalia in 2006.

Abiy, by contrast, portrayed the deal as a diplomatic triumph which fulfils Ethiopia’s decades-long quest for direct access to the sea. In recent months the prime minister had alarmed observers with bellicose calls for Ethiopia’s roughly 120m people to break out of what he has termed a “geographic prison”. Though Ethiopia once had two ports as well as a navy, it lost these when Eritrea, a region to the north, seceded to form its own country in 1993. Since a bloody border war between 1998 and 2000, which deprived it of access to Eritrea’s coastline, Ethiopia has relied on the port of Djibouti for almost all of its external trade. In 2018 it struck a deal with Somaliland and DP World, an Emirati ports operator, in which it acquired a 19% stake in the recently expanded port of Berbera, some 160km from Somaliland’s capital, Hargeisa. Leaders in Mogadishu were furious; four years later the deal fell through.

Abiy has long made plain his ambitions to make Ethiopia a power on the Red Sea and in Bab el-Mandeb Strait, one of the world’s busiest and most geopolitically contested shipping lanes. A peace agreement with Eritrea, for which he was awarded the Nobel prize in 2019, was hailed at the time as an opportunity for Ethiopia to regain tax-free access to its neighbour’s ports. The prime minister also touted an opaque deal with Somalia’s former president, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, for Ethiopia to use four unnamed ports along the coastline of Somalia, including Somaliland’s. Neither materialised, in part because Abiy launched a catastrophic war centred on Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in 2020, and also because the authority of Somalia’s central government barely extends beyond Mogadishu. More recently foreign diplomats and analysts have fretted that Ethiopia’s prime minister, who is by turns messianic and unpredictable, plans to go to war with Eritrea in order to grab a slice of its coast. Now, though, Abiy can claim to have achieved his goals through diplomacy rather than force. “In accordance with the promise we repeatedly made to our people, [we have realised] the desire to access the Red Sea,” he declared in a glossy promotional video released on January 1st. “We don’t have a desire to forcefully coerce anyone.”

For Somaliland’s leaders the deal marks a breakthrough in its three-decade-long quest for international recognition. “Somalia has been using delaying tactics ever since talks began in 2012,” says Mohamed Farah of the Academy for Peace and Development, a think-tank in Hargeisa. “We can’t wait forever.” Their hope is that where Ethiopia goes, the rest of Africa will follow: the African Union is based in Addis Ababa. Abiy also enjoys strong relations with the powerful Gulf states, above all the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Indeed, some foreign diplomats suspect the UAE, which is also close to Somalia’s government, may have played a part in brokering the deal. Its announcement came just as Abiy also played host to Sudan’s most notorious warlord, Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo (better known as Hemedti), whose paramilitary force, flush with Emirati cash and arms, is closing in on victory over the Sudanese army. In this view, an Ethiopian military base in Somaliland is the latest step in a plan to secure a sphere of Emirati influence throughout the broader Gulf region and Horn of Africa.

Further turmoil is likely. Though Eritrea’s rulers may breathe more easily now that Abiy appears to have achieved his goals without resorting to arms, the prospect, however distant, of an Ethiopian navy on their doorstep will hardly be welcome. Djibouti, which stands to lose out from competition for Ethiopia’s trade flows, is also unhappy. The deal will probably also displease Egypt and Saudi Arabia, both of whom are increasingly at odds with the UAE in its bid for regional dominance. To calm nerves, Somalia is appealing to the African Union and the UN Security Council to intervene. But as one Western diplomat notes, “this is an age where, if you’re ruthless and reckless, nobody gets in your way.” It is a lesson that Abiy has long taken to heart. ■

More from Middle East and Africa

Israel’s Supreme Court strikes back

The justices block a controversial law aimed at weakening the power of the courts

Israel prepares for a long war in Gaza

But it is unclear how it will end

The year everything (and nothing) changed in the Middle East

Months of bloodshed have only reinforced the region’s existing woes