Don’t count on a soft landing for the world economy

Inflation has fallen, but vulnerabilities remain

By Henry Curr

For some time the world economy has seemed to defy gravity. Despite the fastest tightening of monetary policy since the 1980s, America’s economic growth probably accelerated in 2023. Europe has mostly weaned itself off Russian gas without economic catastrophe. Global inflation has fallen without big surges in unemployment, in part because labour markets have so far cooled mainly by shedding job vacancies not jobs themselves. As the year ends, optimists who predicted a “soft landing” are taking victory laps.

Yet the world economy will remain fragile in 2024. Though inflation will be lower, it will remain too high. Economic policy still faces an excruciating balancing act. And even if America continues to dodge a recession, the rest of the world looks vulnerable.

Inflation’s recent fall has been a relief to central bankers. But in big, rich economies it is unlikely to continue declining all the way to their 2% targets unless a recession strikes. For one thing, labour markets still look too hot and nominal wage growth too high. For another, economies will have to contend with the effects of more expensive oil. Just when it seemed as if the supply shocks of the pandemic era and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had dissipated, with supply chains unclogged and economies rebalanced, a barrel of oil has risen in price by about a third since the summer, thanks to production cuts in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere. A price fall was halted by Hamas’s attack on Israel. The resulting pricier petrol could raise fears of a “second wave” of inflation.

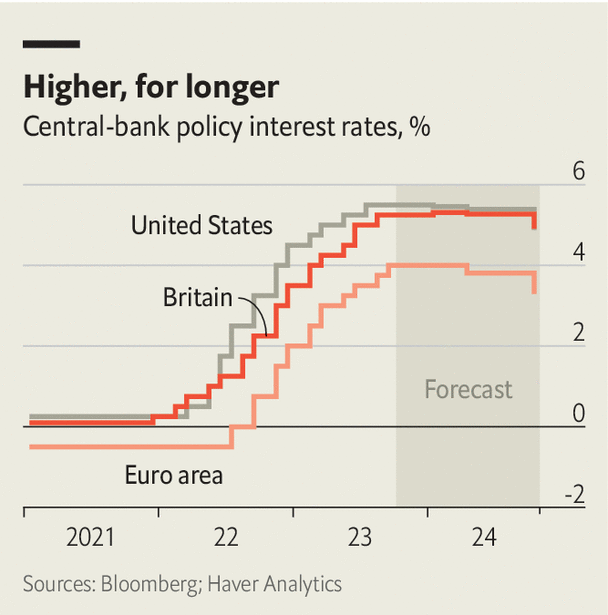

The major central banks will probably not raise interest rates further, instead treating any oil-driven inflation rebound as temporary. But, fearful of premature declarations of victory, they will not be keen to cut rates, either. On recent evidence America’s economy can withstand tight money, even if big companies refinancing debts and households who have run down their pandemic-era savings are beginning to feel squeezed. But high interest rates may be tipping the already-wobbly euro-zone economy into recession, and fear of inflation could stop its policymakers from cutting rates in response.

Even the robustness of America’s economy comes with a big asterisk: it is being supported by extraordinary levels of government borrowing. At the time of writing the federal government’s deficit is running at an annual rate of over 7% of GDP. Debate rages about whether interest rates have entered a “higher-for-longer” regime. The answer depends on whether the borrowing binge continues. It probably will: Congress will not confront it in a presidential-election year. And the first order of business for the next occupant of the White House will be renewing Donald Trump’s 2018 tax cuts, many of which expire in 2025 and which even Democrats will be reluctant to let lapse in full.

Economies without freely borrowing governments look more vulnerable. As well as the likely recession in Europe, the world economy is suffering from China’s growth slowdown. Whether China rebounds and escapes “Japanification” will depend on the degree to which the government continues to open the stimulus taps. But the recent deterioration of China’s economic policymaking—in everything from ending zero-covid to the technology crackdown—suggests it would be unwise to expect a well-calibrated stimulus. And China faces fiscal constraints owing to the indebtedness of its local governments.

All the while, the gradual worsening of geopolitical tensions between America and China, and the global tide of protectionism, are throwing sand in the gears of trade. The number of protectionist measures in place is up from about 9,000 a decade ago to around 35,000 today, according to Global Trade Alert, a charity. Although some economies in Asia benefit from the relocation of supply chains outside China, the duplication of investment and loss of the gains from specialisation are weighing on the global economy’s potential growth. Even winners, such as fast-growing India, show a worrying drift towards homeland economics.

Poor countries that are not in a position to benefit from the redistribution of investment are suffering from high indebtedness, low growth and a strong dollar. In 2024 the IMF will continue to struggle to work out how to provide debt relief to countries that are heavily in debt to China and other lenders who do not subscribe to traditional principles for debt restructuring. And if America’s deficits continue to propel its economy while global growth disappoints, expect the dollar to rise still further, exacerbating their woes.

The possibility of Mr Trump’s re-election to the White House brings the potential for all of these trends to be magnified. A second Trump term would probably mean even deeper tax cuts—and hence bigger deficits—and a further escalation of the trade war. As in 2016, stockmarkets might rally if Mr Trump wins in November, but it would be no good-news story. By the end of 2024 it might feel less as though the global economy has landed softly, and more like the start of another wild ride. ■

Henry Curr, Economics editor, The Economist

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “Soft landing? Don’t count on it”