Demand for “green” metals will redraw the global mining map

The energy transition will mint new fortunes in surprising places

By Matthieu Favas

A net-zero global economy, if it materialises, will not just be carbon-neutral. It will also consume far fewer raw materials. Going from here to there, however, will require a heap of them. In the next few decades, supplying them will create new fortunes.

A planet moving towards a cleaner energy system will still need dirty fuel. And even when oil consumption peaks, countries that can produce high-quality crude at low cost will be strengthened rather than weakened, as their market share and pricing power rise in tandem. Gulf giants such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE will be obvious beneficiaries. Less on the radar is tiny Guyana, where recent discoveries—enough for it to extract 1.2m barrels a day, or 1.1% of global supply, by 2028—could allow it to produce more oil per person than any country in the world.

Appetite for natural gas, a cleaner alternative to coal in fossil-fuel-fired power plants, may last longer still. As Europe has weaned itself off Russian gas, America, Australia and Qatar, which are cranking up output of the fuel in liquefied form, will pocket the proceeds. But so may Argentina. And African countries, meanwhile, could see their share of the global gas market double by 2050.

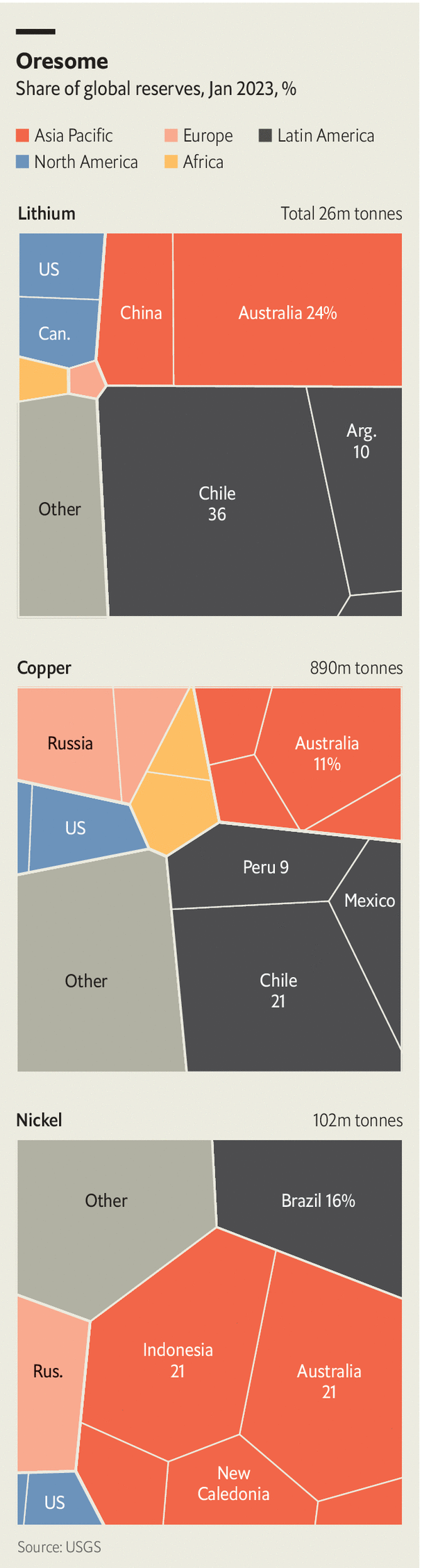

More durable riches may be earned through exporting the billions of tonnes of metal the planet needs to build new, low-carbon infrastructure. Chile and Peru already supply much of the world’s copper; their vast remaining reserves will be tapped as the roll-out of everything green, from wires to wind turbines, boosts demand for the red metal. Declining copper content of ores in ageing mines is raising costs, however, and pushing miners to riskier frontiers. Barrick Gold, a Canadian firm, wants to invest $7bn in a copper mega-project in the volatile borderlands between Pakistan and Iran.

The Democratic Republic of Congo is already well known as the world’s biggest source of cobalt, used in electric-car batteries. Less well known is the fact that cobalt is a by-product of the extraction of other minerals. In recent years that has allowed Indonesia, the largest exporter of nickel, another battery metal, to become a big and growing supplier of cobalt as well. The world’s fourth-largest producer of nickel, by the way, is New Caledonia, a French territory of 300,000 people in the Pacific that holds 7% of global reserves.

When it comes to lithium, the king of battery metals, Latin America, Australia and China look like the obvious champions (Latin America alone hosts 60% of known resources). But they may face unexpected competition. In March, Iran said it had discovered what may be the world’s second-largest deposit. Atlantic Lithium, an Australian firm, is developing Ghana’s first lithium mine. And in September a huge deposit was found in America, on the Nevada-Oregon border. Demand for “green” metals will redraw the global mining map in ways that are hard to predict. ■

Matthieu Favas, Commodities editor, The Economist

This article appeared in the International section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “Full metal jackpot”