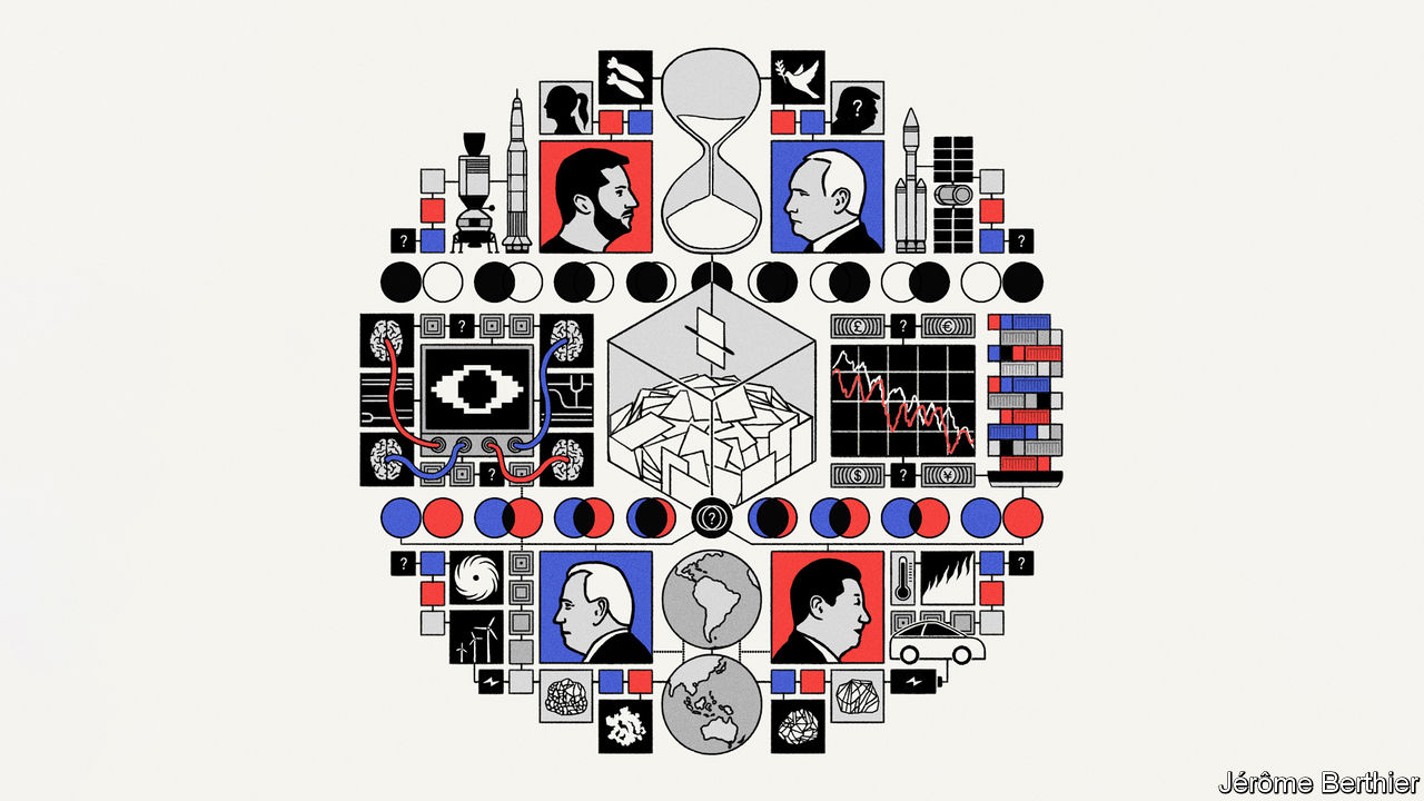

America will need a new vocabulary to discuss its presidential election

Unprecedented, uncharted, not unthinkable

By John Prideaux

Barring unforeseen illness or death, the 2024 presidential election will be a rematch between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. This will be confirmed by the party primaries, which in 2024 will be completed much earlier than usual. Normally the incumbent president is chosen as his party’s nominee without much of a fight. On the Democratic side that will happen again. But the Republican side, where one candidate is so far ahead already that he has been able to skip the early debates, will be much weirder.

In a typical primary cycle, Americans have to wait until the end of March, or beyond, to know who the challenger is likely to be. This time the Republican primary could in effect be finished by the end of February. Americans would then be subjected to a full eight months of a general election campaign between two unpopular candidates—while America’s allies around the globe hold their breath.

If the primaries are less relevant than usual, the attention of politically engaged Americans (particularly those who do not wish to see a second Trump presidency), will shift from Trump the candidate to Trump the defendant. The former president’s federal trial for attempting to overturn the 2020 election starts on March 4th, the day before “Super Tuesday”, when 13 states will vote in the Republican primary.

His campaign will take advantage of this timing, portraying the cases against Mr Trump as a left-wing plot to prevent him from winning a second term and inviting his backers to vote for him (and donate to his legal fund) as an act of defiance. One of Mr Trump’s favourite political techniques is to turn whatever he stands accused of back against his accusers. Thus, while he is actually on trial in a federal court for undermining American democracy, he will claim that the real threat to democratic freedom is the federal court.

The coronations of the candidates will take place in Milwaukee, where the Republicans will hold their convention in July, and Chicago, where Democrats will gather in August to enthuse about four more years of Mr Biden (at the end of which their candidate would be 86 years old). The choice of locations is another reminder of the outsized importance of the Midwest in an election year, and the extent to which the contest to choose the president is not really a national election.

If the vote is close, as most presidential elections are now, then the result will come down to what happens in six states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. This means states with a combined population of 50m people, a bit more than Spain but fewer than Italy, will choose the next president. A bigger swing in either direction could bring a few more states into play: Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Carolina, perhaps even Florida.

The federal cases against Mr Trump are unlikely to be litigated by November 5th, the day of the election, because Mr Trump’s legal strategy will be to delay and then to appeal. As a result, for the first time, America will have a presidential candidate on the ballot who stands accused of federal and state crimes. Words like ”uncharted” and “unprecedented” were worn out by the end of Mr Trump’s first term. America will need new ones for this election.

It is hard to overstate how important the outcome will be for America and the rest of the world. America’s next president will face some predictable problems. The trust funds that pay for Social Security and Medicare (health care for pensioners) are running out of money. Nuclear proliferation in Iran and North Korea will be in the in-tray again. And there is the looming question of Taiwan. China-watchers in the West believe there is a narrow window, which overlaps with the next presidency, during which the People’s Liberation Army would have the advantage in a conflict over the island. The president chosen in 2024 will thus be in charge in the moment of maximum danger.

Most crises, though, are of the unexpected sort. In 2016 Mr Trump campaigned on ending American entanglements in the Middle East. Less than a year later, he gave the order to launch 59 Tomahawk cruise missiles at targets in Syrian territory. The last year of his presidency was consumed by mishandling the spread of a new virus. Mr Biden’s presidency has been steadier and more successful, but the subjects that have demanded most of his attention—the bungled retreat from Afghanistan, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a war between Israel and Hamas—were unforeseen.

A second Trump win, though, would be predictably awful. Plans will be laid over the next 12 months to staff his administration with true believers. The full effect is hard to imagine. What would it mean for foreign policy, or action on climate change? Would other countries elect nationalist populists in imitation again, as Brazil did in 2018?

For America, the questions are even bigger. What would it mean for the country’s democracy to re-elect a man who governed as Mr Trump did, who was impeached twice by the House of Representatives—and who tried to overturn the result of the last election? ■

John Prideaux, United States editor, The Economist

Correction (November 17th 2023): An earlier version of this article contained a dumb mistake. Russia of course invaded Ukraine in 2022 rather than the other way round. Sorry.

Explore more

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “Unprecedented, uncharted, not unthinkable”