A majority of congressmen want more military aid for Ukraine

They are being prevented from voting for it in the name of phoney populism

Ukraine this year officially moved its Christmas state holiday from January 7th, in line with the Russian Orthodox Church, to December 25th, when most of the Western world observes it. But there won’t be much to celebrate. A long-awaited and much-needed assistance package from the US Congress will not arrive in time for the new Christmas, and lawmakers appear unlikely to approve legislation in time for the old one either.

Throughout the autumn pro-Ukraine lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, who form a strong majority in the House and Senate, predicted that eventually Congress would authorise more military aid. Important issues with broad, bipartisan support eventually get a vote, the thinking went. Many expected passage at the end of the year, when big spending packages are often cobbled together quickly, allowing their contents to evade scrutiny and legislators to get home for Christmas.

But Mike Johnson, the House speaker, ran for his job with a plan, “to ensure the Senate cannot jam the House with a Christmas omnibus”. So far that has meant punting the main legislative debates until early 2024. Mr Johnson has a point that passing weighty bills with no time for serious debate is suboptimal. But House Republicans, mired in perpetual infighting and unable to govern effectively with a thin majority, squandered their workdays.

Back on October 20th President Joe Biden requested $106bn to fund Ukraine’s defence, assist Israel’s war against Hamas and “counter malign influence” in the Indo-Pacific. The package also included $13.6bn to fund border security, but Republicans wanted policy changes to tackle what has become a real crisis on the southern border. US Customs and Border Protection reported 240,988 migrant encounters at the south-west border in the month that Mr Biden made his request—up from 185,527 a year earlier.

The House adjourned for the holidays on December 14th, but the Senate stayed in Washington and continued negotiations. James Lankford, Chris Murphy and Kyrsten Sinema—Republican, Democrat and independent senators, respectively—have been working with the White House on a compromise. The negotiators insist that talks are advancing. Yet only 61 senators showed up for votes on December 18th, a clear sign that the Senate would not get legislation through before Christmas.

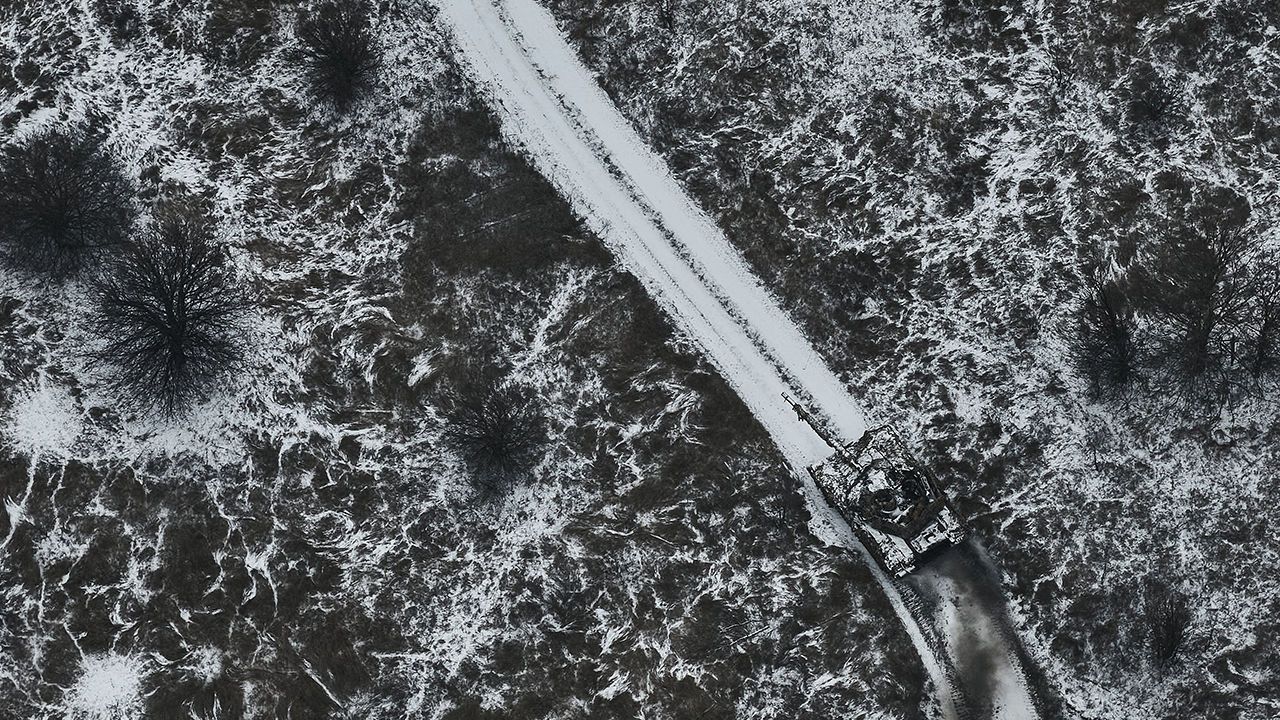

That is cold comfort for Ukrainians who have spent the better part of two years fighting and dying to preserve their independence. The European Union failed to approve a $54bn package for Ukraine the same day that the House left Washington, thanks to the eu’s own functionally pro-Putin blocking minority (otherwise known as Viktor Orban). This has direct consequences on the battlefield. Ukraine, which had been firing nearly 250,000 large-calibre artillery shells per month over the summer, soon will be able to fire at only around a third of that rate. Russia—which has taken defence industrialisation more seriously than the West, while also relying on support from pariah states like Iran and North Korea—will see its advantage grow.

Before lawmakers can tackle Ukraine’s immediate needs, they are trying to resolve a domestic political problem that has vexed American politicians for decades. Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader, cited progress on December 19th but admitted that border policy is “among the most difficult things we’ve done in recent memory”. Mitch McConnell, the minority leader, said that “getting this agreement right and producing legislative text is going to require some time.”

The Senate and White House have not published an outline of negotiations or a basic framework for the compromise. But they are reportedly discussing requiring more mandatory detentions; making it harder to claim asylum; generally granting the federal government more authority to expel migrants; and limiting the ability of the president to allow large groups to enter or remain in the US temporarily. The White House knows the crisis has become a political liability, but the proposed policy changes have not sat well with progressive activists and many Hispanic lawmakers.

Some have even alluded to the gravest transgression in the contemporary Democratic Party: doing something Donald Trump would do. Alex Padilla, a senator from California, warned that “Trump-era policies” would only worsen the crisis. It doesn’t help that such changes would be combined with more funding for Israel, which the party’s left flank has criticised more as the war in Gaza drags on and the number of Palestinians killed rises.

Meanwhile, many House Republican hardliners have unrealistic expectations of the kind of policy victory they can achieve with only a narrow majority in one chamber of Congress. Mr Johnson, one of the most conservative members of the House, lost support from his tribe by preventing a government shutdown and then passing a National Defence Authorisation Act that eschewed fights over social issues. The retirement of his predecessor and expulsion of another Republican made his job even harder, by shrinking his majority further.

Mr Johnson has previously said he would accept nothing short of the Secure the Border Act of 2023, a hardline bill that includes poison pills like resuming border-wall construction. But Senate Democrats won’t support a bill that zero House Democrats backed. Even if the Senate somehow did, that’s not a guarantee that Mr Johnson could win over the most unruly elements of his party for a bill that pairs Ukraine funding with immigration policy.

Slow and painful as negotiations have been, the Senate seems determined to pass a bill. The House returns on January 9th, and most of its members would probably accept a bill that could draw bipartisan support in the upper chamber. The question is, as it has been for months, whether Mr Johnson would allow a vote that expresses the will of the majority of the House, even if that majority doesn’t include more than half of his caucus.

More than 10,000 Americans have served in Congress. Relatively few are remembered in history. Mr Johnson, an accidental speaker, may become one who is. He consistently voted against aiding Ukraine before taking his current role, but he changed his tune after assuming the speakership and has spoken eloquently about the need to stop Mr Putin’s imperialist designs. Will Mr Johnson be remembered as the speaker who defied the will of most Americans and abandoned Ukraine—and also let a border crisis fester—to satisfy the demands of the most radical members of his party? Or will his legacy be as a lawmaker who rose to the occasion, whatever the short-term political cost? He has a long Christmas vacation to decide.■

Stay on top of American politics with Checks and Balance, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter, which examines the state of American democracy and the issues that matter to voters.

Explore more

This article appeared in the United States section of the print edition under the headline "Christmas delayed"

From the December 23rd 2023 edition

Discover stories from this section and more in the list of contents

Explore the editionMore from United States

A clash over Trump’s disqualification tests the Supreme Court

The justices must try to find a way through a legal and political minefield

American pollsters aren’t sure they have fixed the flaws of 2020

That does not inspire confidence for 2024

Kentucky eyes ibogaine, a psychedelic, to treat opioid addiction

The state’s commission may use some of its opioid-settlement money to study the drug