China’s leaders will seek to exploit global divisions in 2024

But they will continue to preach harmony

By David Rennie

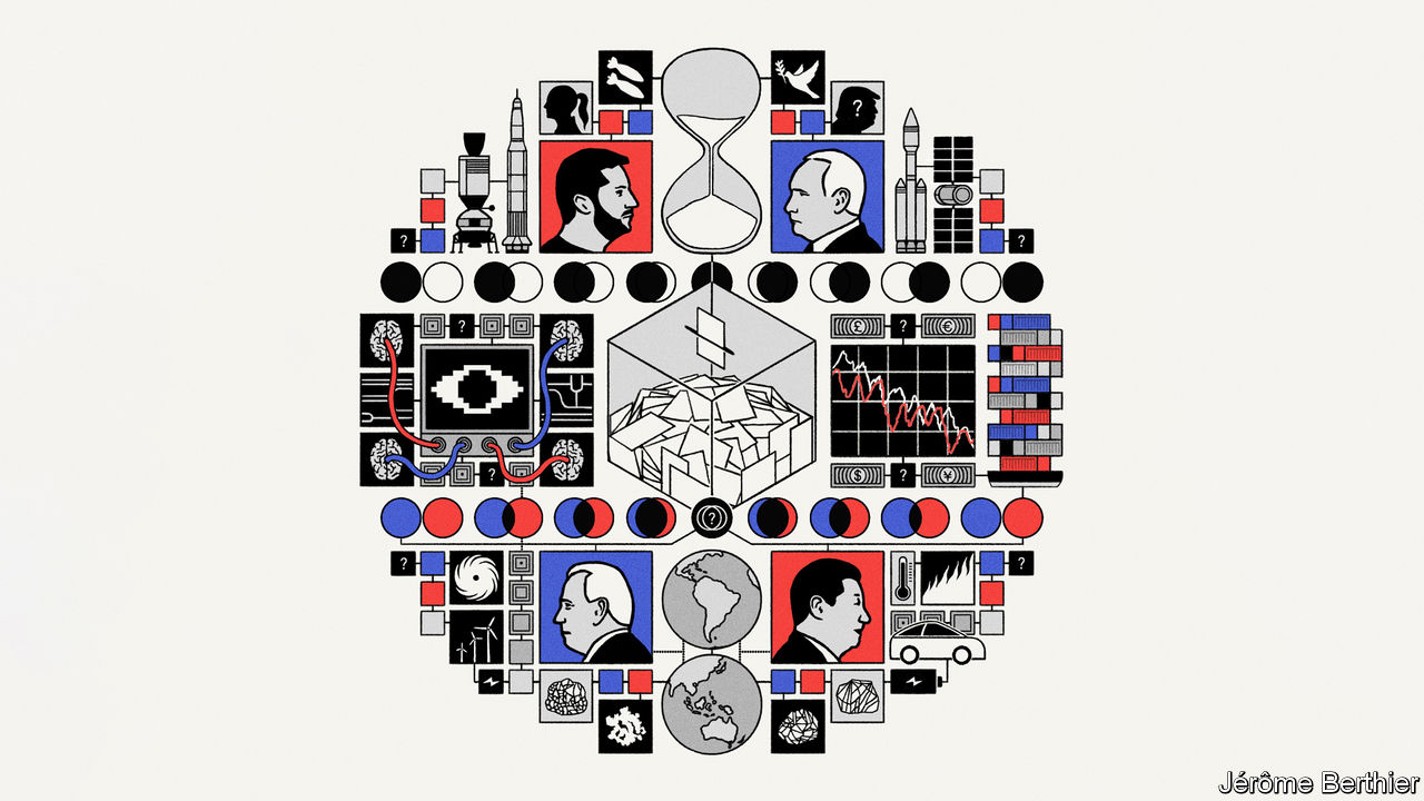

China will pursue two contradictory goals at once in 2024. Xi Jinping and other Communist Party bosses will seek to rally and lead a bloc of countries that are sceptical of an American-dominated world order. But even as China’s rulers prepare for an age of division and great-power competition, they will present their country as a defender of global unity.

To advance their first goal, Chinese leaders will accuse America and its allies of stoking a new cold war. They sense an opportunity to dislodge the West from the centre of world affairs. Their criticisms will have an economic component, too. With global growth slowing, including inside China, leaders in Beijing will charge America and other rich Western countries with erecting protectionist barriers to free trade and imperilling the future of globalisation.

In service of their second goal, Chinese rulers will call their country an upholder of the status quo. By this, they mean that China is a defender of the “basic principles” of the existing world order, as enshrined in the United Nations Charter. This selective reading of the UN’s founding documents favours articles that defer to the inviolability of sovereign states, and downplays those relating to individual rights. Chinese officials will also cast their country as a supporter of the World Trade Organisation, or at least of those WTO rules that opened rich-world markets to China after its accession in 2001.

At times, these twin messages will blur and overlap. Because the rich world still has some know-how that China needs, Chinese leaders will, from time to time, deny that they harbour any animus towards the West. They may offer to co-operate on climate change and other global goods—only, that is, if America and allies stop such hostile acts as condemning Chinese rights abuses or controlling exports of semiconductors and other technologies.

This balancing act is hard. In 2024, it will be made still more challenging by two things: the war in Ukraine and a presidential election in America.

For China, the war offers risk and opportunity. In 2024 Chinese officials will tell leaders from Africa, South Asia and elsewhere that high food and energy prices are caused by Western sanctions, and accuse American arms and energy firms of profiteering at Europeans’ expense. China will claim neutrality in the Ukraine conflict (as it does in the Middle East). It will then deepen ties to the Russian regime of Vladimir Putin, a troublesome but vital partner.

China gains from an isolated Russia forced to turn away from markets in Europe and face eastwards. China is ready to step up purchases of oil, gas, minerals and weapons, paying with its own, non-convertible yuan. Though China’s leaders will not humiliate Mr Putin or challenge Russia as a provider of security in its former-Soviet backyard, they can now expand their influence in Central Asia or the Arctic without fear of a Russian veto.

Should 2024 bring talks to end the war in Ukraine, China will seize the chance to play peacemaker. Mr Xi will be helped by the Ukrainian government’s insistence that he must be at the table, as a guarantor of any possible settlement. In such talks China’s stance will be cold, unsentimental realism. Mr Xi will not endorse any Russian claim to all Ukraine. Indeed, because China claims to set great store by the principle of territorial integrity, it has never recognised Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula in 2014. Instead, China will stress the need to take Russia’s “legitimate security concerns” into account, then offer to help rebuild Ukraine.

The American election in November, meanwhile, poses a dilemma. America’s dysfunctional politics strengthen Chinese arguments that the West is in decline, and that liberal democratic values are a dead end. China, like Russia, will be thrilled by isolationist rhetoric from the candidates, if it signals a return to the sort of 19th-century world order that they favour, with great powers enjoying impunity in their respective spheres of influence. But a wild American campaign presents dangers, as candidates out-hawk one another on China. Arguably, Mr Xi’s best hope is that American democracy looks terrible during the 2024 election, but that China does not dominate headlines. That will require restraint from Chinese propaganda chiefs and “wolf-warrior” diplomats.

Shared resentment of the West is the force that binds China to its closest partners, an otherwise motley bunch. But making that scorn too explicit could backfire, if China ends up centre-stage in American politics. Though Xi-era statecraft is not known for its subtlety, 2024 poses an exquisite test.■

David Rennie, Beijing bureau chief, The Economist, Beijing

Explore more

This article appeared in the China section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “An undeclared cold war”